Crumpets

'Come on, put your shoes on, we're going for a walk.' We never go for a walk. Penn Common is a rolling meadow of tall bracken, moss and the odd thicket of birch trees. In spring there are primroses and in autumn mushrooms. Right now there is just a cold east wind and fine needles of falling rain. My ears are pink. My mother keeps clapping her hands over hers. We never do anything like this.

I am dawdling 20 feet behind them, catching the odd word. 'Not in hospital, at home... ', 'Please, please let me be at home... ', '...be able to cope... ', 'If he was only tougher... '

My father bends his head. 'If the worst comes to the worst...', '...taken into care, it's not like it used to be.'

I guess my mother is pregnant, that she doesn't want to have the baby in hospital and that for some reason it may have to go into care. I rather fancy the idea of a little brother or perhaps a sister.

We walk on, my face getting so cold and numb I can barely feel my tongue. We keep walking, and now both of them have their heads bent down against the stinging rain. My father puts his arm around my mother. He has never done this before. Perhaps she's cold. I think they are crying. Not once do they look back at me.

At home my father tears open a packet of crumpets and toasts them on the Aga. He puts so much butter on them that it runs through the holes and down our arms as we pull at the soft, warm dough with our teeth. We all run our fingers round our plates and lick the stray butter off them. Everyone is so quiet. Both of them have red eyes like white rabbits. I thought everyone was happy when you were having a baby.

The Day the Gardener Came

The one man to whom I wasn't a disappointment was Josh. I loved every moment he was around and would stand at his side as he cleaned the pond of its green duckweed, tugged dandelions from the lawn and snipped the dead heads off Dad's prized dahlias. He didn't do the lawn. Mowing the lawn in wide, green stripes was Dad's job, marching up and down its length with the smell of oil and cut grass trailing behind him. The gardening equivalent of carving the turkey. It said, 'I'm in charge.'

Where my father was cold, Josh was warm. Where Dad would tell me to get down, Josh would pick me up. He would sit me on his lap, bounce me on his shoulders, and sit and talk to me in the garage long after he had finished tying up the honeysuckle or raking the leaves from the lawn. Sometimes I would paint pictures for him, my much practised wishy-washy watercolours of heather-covered hills and window ledges with potted plants on them. He would put them away carefully in his empty lunch box, like they were fragile, ancient parchments and take them home.

If I walked in when Josh was getting changed he'd instantly stop and talk to me, sometimes wearing nothing at all. He started bringing magazines, the two of us straddling the wide seat of his motorbike, him sitting behind me with his arms hugged around me, slowly turning the pages for me. He said it was probably best not to tell anyone about the magazines.

One day I ran into Mum and Dad's bedroom to ask Dad if I could go out and play. Dad hadn't got any clothes on and got cross and told me to knock on the door next time. I told him that Josh never minded when I saw him naked. Mum and Dad glanced across at one another, then Dad looked back down at the floor.

The following week I ran home from school to see Josh as usual. His bike wasn't there, and in the garden was a wiry old man bending over the rose beds, a wheelbarrow full of weeds at his side. 'Who are you?' I demanded, glaring at him, my bottom lip starting to quiver. 'Be away with you,' he snapped. 'Can't you see that I'm busy?'

Mince Pies 1

'Isn't it a bit early?' I say, quizzing Mum over her plan to make the mince pies 10 days before Christmas.

'No, I'm going to put them in the freezer so they are ready for you to pop in the oven whenever you want one.' It's about time we had something in the freezer. Mum is getting shorter, her back seems arched now, as if she's carrying coal and her eyes are tired, spent. Two years ago she was tall, willowy, upright; now it seems like an effort for her to stand. 'Get the rolling pin out, let's get them done.'

The patty tins are rusty, with a faint layer of grease in the bottom of each hollow. I wipe them out with a piece of kitchen paper. I love making pastry, bringing my hands high up in the air as I rub the tiny cubes of cold butter and soft lard into the flour. It's an exaggerated action, but one that gets the air into the pastry and makes it light. We add water, but no sugar, no egg, and pull the ingredients into a small boulder. 'I thought we were supposed to let it rest, Mum,' I chime in, a trick I had read in a magazine of hers.

Mum starts to roll the pastry out, concentrating hard, like every push is a piece of mathematics. 'Here, you have a go, darling.' She hands me the wooden pin with its red handles and goes to the top drawer for one of her Ventolin inhalers. There seem to be more than ever lately. I found one in the map pocket of the car yesterday. She sits down on a kitchen stool, the one with the leg that wobbles, and puts the inhaler to her mouth. She closes her eyes and presses the top down. She calls it her 'puffer'. Every time she presses it down, she seems to jump, like she has been punched in the chest.

I continue rolling the pastry, a wiggly-edged rectangle that looks like a map of Australia. A piece falls off. New Zealand, I suppose. We have a set of red plastic tart cutters with crinkle edges, but only ever use one of them. I cut out almost two dozen over the next 10 minutes, rolling and stretching where I must, patching a hole, a tear, a crack. I push the pastry down loosely into the patty tins. I don't want the pastry to stick. Mum walks over to the larder and there is much clanking and banging, I hear tins being pushed along the shelves, even the Christmas puddings being moved.

'Sorry, honey pie, I could have sworn I had some mincemeat, we'll have to put it all away in the fridge till tomorrow.' Mince Pies 2

'But Mummy, you promised!'

'Darling, I'm sorry, I forgot to get it when I went to the shops.'

'You're hopeless, I hope you die.' I run up the stairs to my room, slam the door and lie face down on the bed. I knew she'd forget. I just knew it.

The Night Just Before Christmas

It is a couple of nights before Christmas, about five in the morning, and I'm snuggled down under the sheets. I'm warm in my striped winceyette pyjamas and soft cotton bedding, my bedspread pulled up tight around my ears. Toasty. Outside, the thick frost still twinkles under the street lights. Deep silence. There are flakes of frost around the edges of the glass in the bedroom window. I can feel my warm breath on the back of my hand.

If I stretch my feet out, right down to the bottom of the bed, I can, with pointy toes, feel a heavy weight. Something told me Santa Claus would come early this year. What with Mummy so desperately poorly - I heard the doctor say something about oxygen tanks last night and my father kept holding his forehead in his hand, his thumb pressing on his right temple - and everyone looking so miserable, he knew we all needed cheering up. This means I get my presents before anyone else, and the ones under the tree can wait till after Christmas lunch.

My Christmas stocking is actually a cotton pillowcase. Father Christmas always leaves it at the bottom of the bed. Last year there was a cuckoo clock and a sort of glass globe with metal paddles inside that went round in the sun but stopped as soon as it got dark. There was a Spirograph, a green MG convertible for my Scalextric track, more Lego and Meccano pieces, a string frog puppet, a set of short coloured chalks which I loved and a pair of football boots which I didn't. The boots had blue plastic studs. No one else at school had boots with blue plastic studs. Just me. They sounded like high heels when you walked in them. David Woodford laughed at them. Maxwell Mallin laughed at them. This year I'm hoping for my own copy of A Hard Day's Night and a pair of Hush Puppies. The brown suede ones with the black elastic on the side like Adrian's.

I push back the bedspread and the warm cocoon of brushed cotton sheets. There is no bulging sack and casual scattering of beribboned boxes. No round lump of clementine in the far corner of the pillowcase, no Cadbury's Selection box in the shape of a sock. Just Daddy, kneeling, his elbows resting on the bed, his head in his hands. Sobbing. He climbs further on to the bed and wraps his arms tightly round me. I bury my face in his soft Viyella check shirt.

Walnut Whip 1

I learnt to love the woods. Not ours with its neat rows of carefully pruned Christmas trees, but the woods further up the road, which were less dense and had chaotic mounds of brambles with more blackberries than you could eat. I would walk for hours at the weekends, coming back with Tupperware bowls of berries which Joan made into pies with Bramley apples from the garden.

The woods were quiet; sometimes I would see no one all afternoon. It was here I would sit and read Cordon Bleu magazine or the cookery pages I tore out of Joan's Woman's Journal, and where I would masturbate, sometimes two or three times in an afternoon. Occasionally, I'd find pages torn from porn magazines that others had left there, pictures of big-breasted women with beehive hairdos and men with moustaches and medallions round their necks.

Dad continued buying us sweets to eat in the evenings. A Cadbury's Flake for Joan, a Toffee Crisp or Walnut Whip for me. He would usually just have an Aero and his pipe. My bedtime was at nine, even during the school holidays, and before that I had to take the dog out for his nightly walk. The road was narrow and the cars would come hurtling round the bends, often just missing me and the dog on his long lead. It seemed daft to take the dangerous route when it would be much safer to walk in the other direction, but I was forbidden from going up to the reservoir.

'It's not safe up there, the cars come at a hell of a pelt,' was the old man's stern warning. In truth, the cars had a much clearer view of any pedestrian and the chances of being run down were much slimmer than the way I had been told to take.

I had no idea about the lay-by near the reservoir. I knew it existed of course, and that at night cars would line up to look at the twinkling lights scattered round the Malvern Hills like diamonds in a necklace. On a frosty night you could see even further, each light sparkling in the cold night air that made your face feel like a peeled grapefruit. Tucked up watching the news, neither Dad nor Joan were likely to leave their chairs and no one would know if I took the reservoir route. And anyway, I could let the dog off his lead in the lay-by.

Once the lead was off I curled it up and stuffed it in my pocket, pulled apart the cellophane bag of a Walnut Whip and bit off the walnut. I could see a row of cars all facing the glittering lights of the hamlets and villages below. The river shone like an abandoned silk scarf in the moonlight. People were sitting in their cars talking, some with their arms around each other. One car, a pale green-and-white Ford Capri, appeared to have no one in it, yet was swaying violently back and forth. A foot or two closer and I could see a pair of knees, wide apart, and then a slim, bare back. Within a foot of the car I got a view of a mechanically thrusting bottom.

I must have stayed there seven or eight minutes, heart pounding, mouth parched, licking the filling from my Walnut Whip, wishing it was an ice lolly and praying the dog would stay away. Then a car door opened on the other side of the lay-by and I ducked down by the driver's door of the Capri. A guy was standing with his back to me, peeing into the hedge. I couldn't believe how he couldn't hear my heart thumping. He got back into his car. The dog spotted me crouching and came scuttling towards me. I pushed him away then stopped when I could see he thought this was the start of some new game. The Capri suddenly stopped moving, I twisted my head round and looked gingerly up. Slowly, the driver's window opened an inch or two and a hand pushed something wet and glistening out of the window. It landed on my back, then, a second or two afterwards, a tissue followed. I shook myself, grabbed the dog by his collar and half ran, half walked, back down the hill, my heart hitting my ribcage, dropping the last bite of chocolate, the bit with the second walnut in it, behind me.

I was still panting when I pulled back the curtain that acted as the door to the cloakroom. 'All done then?' asked Dad as he walked over and I hoicked my jacket up on to an empty peg. Then, as the light from the kitchen door flashed into the dark world of coats and wellington boots, he peered over the top of his bifocals and asked, 'What's that on the back of your jacket?'

'Oh, that ruddy dog,' I said, my stomach doing a sick-making somersault. 'He's been slobbering everywhere again,' and I discreetly wiped a thick, shining line of semen off the back of my school blazer.

Toast 2

'I want to talk to you about something,' says my father ominously and with one of those smiles that somehow manages to both scare and patronise me all at once. We walk out into the garden and round the rose beds, him pretending to look closely at each pink-edged Peace rose, me silently cringing, hoping desperately he isn't about to say 'man to man'.

'I've asked your Auntie Joan to marry me and she's said yes,' he says in a calm, no-messing sort of a way, squishing a greenfly between his thumb and forefinger as he does so and wiping it off on his trousers. 'I think she's just like Mummy, don't you?'

I just stand there, intently examining a fully open rose, not knowing what to say. Mummy hadn't ever smoked or said 'bleedin'. Neither had she cleaned houses for a living or bought clothes from a catalogue. I don't think she had ever set foot in C&A, let alone bought a coat from there. Mummy never wore mascara, or perfume bought from a woman who came to the door, or walked around in a quilted nylon 'housecoat'. I had never seen Mum with curlers in her hair or putting her lipstick on at the table. Neither had I ever heard her say 'arse'.

Mummy hadn't drunk snowballs or collected cigarette coupons, she had never cut tokens from the back of packets or stuck Green Shield stamps in a book. Mum had never played bingo and didn't have yellow nicotine stains on her fingers. I am sure she would never have worn anything made of brushed nylon. (Mum wore mushroom-coloured clothes and had shoes and handbags that always matched. I had never seen her without a brooch. Mum always said 'touch wood' after she had tempted fate and 'bless you' if I sneezed or farted. She said 'oh heck!' rather than 'bugger, bugger, bugger'.)

Mummy never used my father as a threat to get me to do what she wanted, neither did she hug me when he was looking yet freeze me out when he wasn't. Mummy had never had a 'blue rinse' put on her hair or clear varnish on her nails. Mummy never said 'nigger brown'. Mummy never used air freshener.

I just keep staring at the rose, the petals, the long yellow stamens, stem, the fat red thorns, wanting to say so much. Wanting to tell him how the woman he is going to marry nags me from the moment I get up in the morning till I go to bed; how she makes me wash up my mug the second I have finished my coffee, dry it and immediately put it away in the cupboard; how she always makes me write out shopping lists and fill in forms for her because she says, 'I haven't got my right glasses on'; how it takes her a good five minutes to sign her name on his birthday card, leaving a gap between each letter. And how sometimes we have to start again because she gets it wrong. I am desperate to tell him how I caught her looking through the files in his desk marked 'bank statements' and how she once said she couldn't wait to get back to where she came from, only this time, 'I'll have my own house, not one off the council.'

Most of all I want to tell him how she won't let me make toast when I come in from school, how she says it is because I will make crumbs and she has spent all day 'cleaning his bleeding kitchen'. I want to tell him that there is no one on this earth less like Mummy.

Fillet and Rump

The kitchen looked out on to the gravel car park and then to the wide field that led down to the river. 'No children in the bar' meant exactly that and they would often sit in the car park with pint glasses of lemonade while their parents drank in the lounge bar with its wood panels and hunting prints. There was one girl, older than the others, with piercing violet eyes and dark hair that straggled down over her shoulders, who would sit in the passenger seat of her parents' Humber Hawk for hours, sometimes reading, other times just staring out at the other kids. No one ever brought a drink out to her. Whenever the smoke of the grill became unbearable I would stand in the car park with a lime and lemonade, or sometimes a shandy, and she would look up from her book and smile.

Whenever drinks were poured by mistake they were brought into the kitchen for the staff. By the end of the evening we had swigged our way through a rum old mixture of sweet Martini that had been mistaken for dry, cider and, best of all, gin and tonics when the customer just suddenly disappeared. Mr Beckett, ever under his wife's beady eye, would sometimes bring in a brandy and Babycham for Di, claiming it was a mistake. Funny there was always one about the same time each night. One night a tray of drinks arrived in the kitchen - the result of someone doing a 'runner' - with only Diane and me to drink them. I took a couple of them out to the girl in the Humber, who received them with a smile that was cheeky, quizzical. She knocked them back like I had only ever seen anyone do on televison. Later, when I overcooked a steak, I ran out into the car park with it, wrapped up in napkin, and gave her that too.

I started to watch out for Julia, at least I knew her name now if nothing else, and started cooking bits of fillet specially for her; the tail end perhaps, or a slice that had been cut too thin. 'Don't cook it so much next time,' she would say, with the same cheeky grin.

'I think someone fancies you,' said Diane one particularly sticky evening in late July. 'Your friend has been peeping at you all night.' And then, 'Go on, go and see her, I'll be all right if any orders come in.' I didn't like to tell Diane she was probably just looking for her supper. And so it went on for three weeks, me sneaking drinks and medium-rare steaks to Julia in a soggy napkin, taking my breaks leaning against her car door, she talking to me through the open window while she tore off bits of steak.

Nights off were long, silent, intolerable. I would sit at home in the cold dining room, Joan watching The Golden Shot or Randall & Hopkirk (Deceased), Dad out at one of his Masonic 'dos'. Only now it was the summer holidays and there was no homework, no excuse to be anywhere but sitting with her, or her and him, festering, while he sat in the chair in front of the telly, she on the floor snuggled between his legs. One night I lied about having to go to work, then walked down the hill to talk to Julia all night.

'Why don't we walk down to the river?' she asked. We walked, without speaking much, clambered over the stile and through the paddock towards the river and the oak tree whose roots came up through the mossy soil like a tangle of serpents. We sat there, our backs flat against the trunk of the tree for an hour or more. Saying nothing much, picking up the odd acorn and chucking it at nothing in particular. At one point we said nothing for a good 10 minutes. Welcome washes of cool breeze would come from nowhere, then disappear again leaving the air hot and heavy as lead. Still we said nothing. I wasn't sure what, if anything, I should be doing. In the lay-by I had seen more shagging than you could shake a stick at, but I wasn't sure what was supposed to happen before. I hadn't bothered to watch the cars where nothing much seemed to be going on. Then quietly, almost matter-of-factly, Julia just said, 'You'll have to hurry up. I've got to get back soon.'

We spent the remaining weeks of the holidays in a sort of steak-for-sex deal that seemed to suit both of us. Everyone called her my girlfriend, but she wasn't. It was just steak, snogging and shagging. Same place, same time. Life was pleasingly neat, tidy, predictable. I grilled steaks, stuffed prawn cocktails into wine goblets, defrosted coq au vin and learnt to make Irish coffees, a thick layer of cream floating magically on the sweet, black, whisky-laden coffee. I got into the habit of deliberately getting one wrong, the cream swirling down through the coffee just so I could have one before going off with Julia. I stashed away every penny of my wages in an old cigar box hidden behind my collection of the Children's Encyclopedia. I saw Dad and Joan only long enough to walk through the sitting room on my way upstairs to bed and to pick up my perfectly ironed clothes from the airing cupboard. Neat, tidy, predictable. And then Stuart turned up...

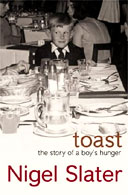

· To order a copy of Toast, by Nigel Slater, for £14.99 plus p&p (rrp £16.99), call the Observer book service on 0870 066 7989. Published by Fourth Estate. Next week in OM Magazine: sex, syllabubs and sliced rare roast beef sandwiches