It's not yet midday and already, on this Thursday morning, a small queue is forming outside a modest restaurant in Farringdon, London. Three Japanese students clutching an A-Z; a couple of silver-haired businessmen in expensively tailored overcoats; a woman on the phone, urging her errant lunch companion to get a bloody move on.

By 12.45pm the place is pretty much full; half an hour later they're turning customers away. Those inside are chowing cheerfully down on steamed mussels with shallots, parsley, white wine and cream or pressed foie gras terrine with brioche and fig compote; whole poussin with gratin potatoes, lentils and peppercorn sauce, and paupiette of salmon with avocado and tomato salsa.

It's not haute cuisine, but it's really not bad.

"Sorry," mutters Silver-Haired Businessman Number One, who's opted for the crab tartlet with saffron cream dressing and mixed leaf salad. "We're doing cheap at the moment. And how!" No problem at all, replies his contact. Quite understand. "And actually I rather like this place. Bit of a trek, of course, but the food's fine. And cheap, Roger ... cheap really isn't the word for it."

These are great days for restaurant-goers. The reservations website Toptable greets you with the heartening news that in London alone, there are currently 292 restaurants offering a total of 496 special deals. These range from places proposing simply to knock 50% off your bill, to Michelin-starred gastrodomes such as L'atelier de Joël Robuchon or Arbutus with lunches for about £20. Even the Ritz has a six-course, credit-crunched black truffle menu for a mere £90. Imagine!

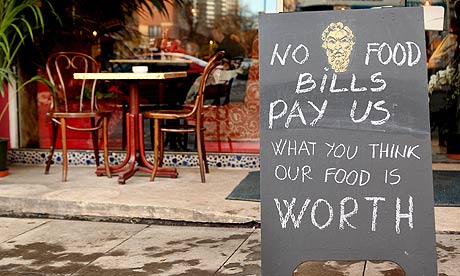

Peter Ilic has gone a step further: lunch at his Little Bay restaurant in Farringdon is free. Well, not completely; he charges you for your drinks. But the bill, when it arrives, has a blank space where the food charge should be, and next to it the words: "Please state how much you would like to pay, and how much you think your meal is worth."

Ilic, a likeable and canny Serb who's run restaurants in London for more than 25 years, has been operating his no food-bill regime for a fortnight now and reckons he's comfortably ahead. "Hardly anyone leaves nothing," he says, "and then it's more like a dare, to see if they can really do it. Some leave £35 for three courses. It's fine. I'm more than happy." His eccentrically decorated 130-seat restaurant used to serve around 1,100 punters a week; he's now doing 2,000, and turning people away.

But as the recession begins to bite, Ilic is a rare bird in restaurantland UK. According to the consultancy PricewaterhouseCoopers (PWC), 141 restaurants went bankrupt in the last three months of last year, and the trend is likely to intensify this year. The restaurant consultant and food writer Nick Lander goes so far as to suggest we'll soon stop using the word altogether: "restaurant" spells expense, luxury, frills-not-food.

There have been big-name casualties: last week, predicting turmoil in the restaurant business and blaming the banks for refusing to extend his overdraft, celeb chef Anthony Worrall Thompson closed six of his establishments with the loss of more than 60 jobs.

Two of Jean-Christophe Novelli's gastropubs recently ceased trading; Northern Ireland's biggest TV chef, Paul Rankin, is reportedly on the brink of failure, his mini-empire reduced to just one Belfast eatery; Raymond Blanc has shut down his Manchester outpost, Brasserie Blanc; young Tom Aiken only managed to salvage his business by saddling his creditors - mostly small independent suppliers - with some £3m of debts, and even a couple of the rambunctious Gordon Ramsay's lesser ventures have been advertised for sale (in error, apparently, but who can really say?).

"Eating out is much more firmly entrenched as a habit now than it has been in previous recessions," says Stephen Broome, of PWC. "But people are still going out less often, they're going to spend less when they do, and they're going to look for substitutes maybe one weekend a month."

Supermarket offerings such as Marks & Spencer's "Eat in for a tenner" - a bottle of wine and a three-course meal for two, for £10 - can start to look mighty tempting, as can the option (spurred by the likes of MasterChef, which seems to be on TV pretty much every night of the week) of just staying home and cooking for yourself. Sales of raw ingredients from local shops certainly lead analysts to believe "aspirational home cheffing" is on the increase, PWC says.

So what, in these straitened times, does a restaurant need to do to stay in business? First, be very nice to the customers it does get. "The reign of the clipboard Nazis is drawing to a close," says Richard Harden, jovial co-founder of Harden's Guide. "For far too long, there's been an attitude in some restaurants that you're lucky to be eating there. All those haughty reservations managers and indifferent staff are now well aware, I think, that if they want to stay in work, that's not the way to behave."

Stephen Hanson, a leading New York restaurateur, calls it "hugging the customer", and very nice it can feel too. I was lunching at the modest but very good Fish Hook in west London recently (credit-crunch lunch deal: two courses for £12.50, three for £15), nipped out to take a call in the middle of my soup, and came back to find the waiter politely holding my napkin, ready to spread it over my knees when I sat down.

A colleague was at the much grander Murano, Angela Hartnett's highly-acclaimed Mayfair eatery, the other night, nearing the end of her "unbelievably delicious" venison: one small morsel left, but none of the spectacular sauce that had come with it. "Madame," the waiter apparently inquired, entirely unprompted, "would you like a little more sauce?" The service was "probably the best I've ever had", my colleague says. "It just made you feel very looked-after, very special."

Equally if not more important, restaurateurs agree, is perhaps the most basic requirement of all, the one best formulated by the great 18th-century French foodie Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin in his still-readable Meditations on Taste: a good gastronomic experience boils down to "fine ingredients, cooked simply, eaten in convivial surroundings". And it helps, Brillat-Savarin would, I feel sure, have added had he spent the past few years dining out in some of Britain's so-called better restaurants, if you don't feel you've been ripped off afterwards.

"Of course you need really considerate service, you need to bend over backwards to make sure you give 100% to every client who walks through your door," says Michel Roux Jr from the kitchens of the two Michelin-starred Le Gavroche, arguably Britain's finest French restaurant. (Roux says his restaurant's footfall - the number of diners coming through the door - is pretty much stable, but takings are slightly down, largely due to customers spending less on wine.)

"But what you also have to provide in a recession is recognisable, hearty, flavoursome food, the kind of meal that will leave your customers feeling they've really filled their bellies and they feel good," Roux says. "You don't get that kind of food in all these flash, cooking-by-numbers kind of places. People want certainty; they want to know they'll get good quality, and that it will be good value for money."

Value for money, of course, can come at £10 a head, £35 a head or £100 a head: the important thing is that the punter doesn't feel disappointed. "You want to offer straightforward, honest food; comfort food, really," says Herbert Berger, chef at the Michelin-starred 1 Lombard Street, familiarly known as the City Canteen. Hit by a slump in corporate entertainment spending, he's offering a five-course evening meal (quiet time in the City) for a reasonable £19.50.

"Special deals are all well and good, but you need to give quality, and value for money. Cheaper cuts are in - food that's often better to eat anyway," says Berger. "It's about hospitality. A lot of places are going to be in trouble, there's no doubt. A lot of fake places, places with high-profile names behind them that did OK during the boom years, they'll be going."

Des Gunewardena, head of D&D, the firm behind the 23-strong Conran restaurant empire that includes Quaglino's, Le Pont de la Tour and Launceston Place, speaks of a "flight to quality, and a flight to value" since "that Lehman weekend", when one of America mightiest investment bank's went belly up. Restaurants must give customers "an experience that's worth the bill they get", he insists; those that survive will not necessarily be those lauded in guides or on websites, but those "whose customers are happy, and come back".

It's a theme echoed by Thomasina Miers, former MasterChef winner and now behind the Mexican-flavoured Wahaca, which still has punters queuing round the block. "We've got no special deals," she says, "but we're cheap: £13 without wine. It's simple, what counts is really good quality food and first-class service ... Just because you're cheap, doesn't mean you can't do both of those. And the good thing about all this is that London restaurants' prices have been so absurd for so long, but now the consumer can really get on top of it."

The consumer is certainly on top of it at Little Bay. Out on the pavement, a party of three contented customers confess that excluding the wine, they'd left a grand total of £24 for two courses each. They will, they say, be back tomorrow. And next week. A bargain, and damn nice food.

Meal deals: fine dining has never been cheaper

St Alban, Regent Street

Universally acclaimed food and service; walls decorated by Damien Hirst. Two courses for £15.50 (three courses for £19.75), early and late evening.

Tom Aikens, Chelsea

Michelin star. Impeccable French cuisine. Two courses for £23 from a set menu. Evenings, not Saturday.

Livebait, Manchester

Brasserie-style fine fish and seafood. Two courses £14.75, from a set menu. Evenings, not Saturday.

66a @ The Cotswolds Lodge, Oxford Elegant decor; seasonal ingredients. Two courses £12 from the set menu, lunch; 2 courses £15 from the set menu, dinner. Not Saturday.

Malmaison Brasserie, Newcastle

Chic brasserie; excellent locally-sourced ingredients. Two courses and a bottle of wine £29.00, from the set Home Grown and Local menu. Sunday to Thursday.

• Deals through toptable.co.uk