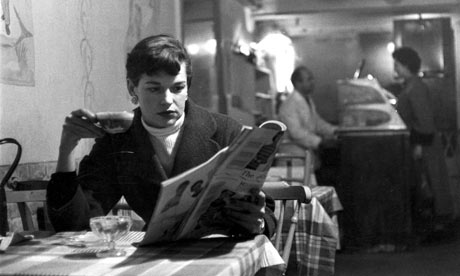

KATHARINE WHITEHORN

on peaches eaten over the sink and taramasalata on toast

Gourmets and cookery writers cook because they are fascinated by food and cooking; most of the rest of us cook because someone needs feeding. But what happens when the somebody is yourself? When you live alone, or when all the others are out?

A woman who has gone from trying to impress a mate with gourmet delicacies, had her Elizabeth David impulses crushed by the vats of spaghetti sauce and slag heaps of mashed potato demanded by children and finally finds herself alone may keep her old standards. The man who eats out, grabs sandwiches and ready meals might, from time to time, decide to tackle the cooking of a Real Meal. But the chances are that the shape of the whole thing will be markedly different from the family cooking or suppers for two that cookery pages aim to inspire. There'll be more baked beans, for a start. The usual difference between the meals of those only occasionally on their own, as opposed to those who live alone, is, on the contrary, their wonderful guilty feeling of indulgence. Wicked snacks tend to figure highly: smoked salmon for some, Cornish pasties, both halves of an avocado, just one more left-over mince pie…

Ask them what is their favourite and a glint comes into their eyes: "Toast, and cheese – any cheese – topped by sweet onions," rhapsodised Claire Rayner when I asked her – and then went on at length about the exact nature and provenance of the right sort of sweet onions. "Taramasalata – I dip carrot sticks into it," sighed Katy Bravery, editor of Saga magazine and a wife and mother off duty (me, I just eat it on toast). Teenagers – at least the males I used to have about the house – eat bowls of cereal at odd, very odd, hours. And several women I know have to hide the chocolate biscuits where they're a real trouble to get at; it doesn't work, of course, any more than hiding the bottles helps an alcoholic; no one has ever used up as many calories hunting for chocolate as the chocolate itself provides.

It is not just the food, but mealtimes that have an importance for people kicking about the house alone: they give a shape to the day. The news programmes figure greatly in this: I can eat once it's the one o'clock news, have a drink with the BBC six o'clock – ITV used to provide a rather helpful one for a bad day at 5.35pm, but the rotters dropped it. (I can't see what the point of 24-hour news can be except for registered alcoholics.)

I suppose I've been concerned with people who cooked for just one for almost 50 years, since I was told to write a book for those living in bedsitters. In those days the food scene was amazingly different – I had to explain what an avocado was and urge the merits of the tea bag; there was little in the way of takeaway food and, above all, the young in such places would never have had a fridge. I don't know whether the Pope was right when he said the washing machine had been more liberating than contraception – I assume he's never tried either – but for us in the developed world it is fridges and freezers that surely have made a fantastic difference. Before, you had to buy much of your food quite near the time of cooking and try to eat it up before it dried up or went green; it was hopeless to try and make a great potful of something and eat small helpings of it over the weeks. Now a good many people on their own make huge baths of chilli or mince or homemade soup to eat bit by bit over weeks. And having put them in the freezer themselves, they may even be able to remember what those little packages originally were – you can never identify other people's UFOs, their Unidentified Frozen Objects.

The whole food scene could hardly have been more different in the early 1960s when I wrote Cooking in a Bedsitter. Mostly people had just one ring, or at most two, to cook on; so much of the best grub was cooked all in one pot. Many of the best recipes were adapted from a book called Casserole Cookery by Marian Tracy, the premise of which was that what every sensible cook wanted was just to shove something in the oven and get back to the drinking.

There's not a lot of that about these days: things are immeasurably easier now. We didn't have the all-time useful wok, or microwaves, and of course there weren't the endless varieties of ready meals you can now get almost anywhere. A lot of people living alone use them in conjunction with something else – rice, particularly: artist Martin Davison buys one big ready-made curry and enlivens several helpings of rice with it, or a soup to which he adds – well, almost anything, I think. Davison was also the originator of "Martin's lifesaver (only 3,000 calories a helping)" for the bedsitter book; it consisted of wholemeal bread, thickly buttered, with strawberry jam, double cream and grated dark chocolate: "Leave in a warm place to recover (you)".

He is a bloke, and thin; the trouble for a lot of us lone females is that if we ate what we really like best, the resulting extra weight would break the scales; so perhaps I should pay tribute to philosopher Marianne Talbot, who has recently lost pounds and pounds by eating every evening just a large bowl of salad and a small lean steak. Opera writer Henrietta Bredin says you simply mustn't have the fattening stuff in the house at all, especially if you work at home; raw vegetables are safe – even I, passionate about potatoes, can't nibble on them raw – and she adds different cooked vegetables to Japanese noodles (not pot noodles, she sternly adds). We have our standards; they may not be high, but we who eat alone have them.

We do pretty well; we certainly don't starve. But cooking, at its most pleasant, is an audience thing. You want someone to appreciate it, to be pleased; the Observer's great innovative woman's editor George Seddon thought of cooking as "a way of showing your love for someone without actually talking" – well, that's one way of looking at it. Without an audience, all you want is to find something nice to eat with the least trouble – unless of course you're putting off doing something else.

Many of us will pick up any snack we can get hold of, with a strong tendency to have grandiose plans which still end up as an omelette, or a sandwich, again; but some do insist on excellence. Rosemary Stark says she never buys ready-made food – "Well, I am a cookery writer". Ready- made stuff is eschewed entirely, too, by Angela Malik, the only woman I know who took up serious cooking when her husband – Michael Malik (who wrote for the Observer) – died. Way back when, she had cooked for her children, but when she and Michael retired it was he who adopted gourmet cooking as his hobby. She says she does simpler versions of what Michael cooked – she has her own version of his Madhur Jaffrey curry, roasts lamb chops instead of a leg; she does go so far as to put together a bacon sandwich or two, but says she cooks even fish pie or chilli with very great care because "I can't bear awful food".

I rather doubt if many singletons are so strict, but I remember that when, long ago, I wrote an article on "What Bachelors Eat" there were quite a few exquisite gourmets who did clever little meals for themselves – I could just see them shooting their exquisite cuffs as they carefully warmed a plate or consulted their copy of Edouard Pomiane's Cooking in Ten Minutes.

Probably more common, I felt, was the attitude of lawyer and thriller writer Michael Underwood, who had always been cooked for, first by his mother and then a devoted old housekeeper. When both died, his normal dinner plan, he said, was: "I eat the pears out of the tin standing at the sink, while my bought shepherd's pie heats up in the oven." I got the impression that this was always what he ate.

Sometimes I wonder if the really big distinction between one person's taste and another's is not so much whether they like spicy food or bland, whether they eat four times a day or once, whether they are gourmets or happy pigs; but whether they want variety and choice in what they eat or whether they'd rather, actually, just eat the same thing over and over and over again – which usually only those on their own can do.

And like Michael Underwood we can eat our food in any old order – why, after all, do people eat fruit first at breakfast and meat first later on? Why do Greeks and Scandinavians eat cheese at breakfast, but not us? It's all a matter of habit – and if some of our habits are regrettable, well, there are some advantages to our state, after all: we do what we like.

JAY RAYNER

on eating out alone

Eating alone, like train-spotting and stalking celebrities, gets a bad press. It's regarded as a sad pursuit for sad people with tragic lives and a touch of halitosis – and it's easy to see why. Here is a dispatch from the very frontline of solo eating, and it ain't pretty. It was a winter's night in Birmingham circa 1994 and I had just pulled off a journalistic coup – something to do with MI5 and dodgy photographs – and I wanted to reward myself. Obviously a reward meant food, so I called an Italian recommended by a local listings mag and cheerfully asked for a table for one. There was a snigger from the end of the line, a brisk: "Not tonight, sir." And then they hung up.

I stared at the receiver, baffled, before pushing on. I called a Chinese place and got a similar response, and some French bistro in Edgbaston, before in desperation I called the American-style brasserie that even the dodgy local listings mag seemed to hate. There was another sharp intake of breath. "Trying to book a table for one on Valentine's night, mate? That's tough." I hadn't noticed the date.

I ended up in the restaurant of the Holiday Inn, Birmingham, where I was staying, eating the breast of a duck that probably died some time during the decade before last, of natural causes. It had all the texture of my sofa, but none of the flavour. As I entered the restaurant the man in charge – maître d' would be pushing it, and we both knew it – said: "And would sir care for a magazine?"

The only other time that happened to me was in the treatment rooms of a high-end fertility clinic, where at least they had something I actually wanted to read.

It's all there, isn't it: the pathos, the rejection, the funereal pall. The remarkable thing about this experience, however, is that it did not put me off. All it did was convince me that while eating alone can be a wonderful thing, the circumstances have to be right. That evening they simply weren't.

Here is what you need to know. As with any other solo pursuit, eating alone requires a carefully balanced combination of commitment, enthusiasm and self-adoration. It should, after all, be a meal with someone you love. Hell, if you go out for dinner by yourself and discover you don't like the company, you really are in trouble. So you need to be in a good mood. I regard myself as a gregarious man. I like people and their chatter but sometimes the conversation I really want is the one with myself – we never disagree, me and I – and that happens best over food.

I learned this early – about 6.30 one evening, as a matter of fact, in the dining room of a hotel on the Swiss-Italian border. I was 11 years old, on a school skiing trip and sodden with homesickness. The hotel restaurant's snails in garlic butter, served on a burner that made the pools of fat smoke so that you could fry your bread in them, were the perfect cure for a north London boy whose upbringing had been unapologetically cosmopolitan. I have told the story often – the bemused look on the face of the waiters at this child, melon-belly to the table edge; the repeated visits night after night; the way the molten butter eventually ignited and the whole contraption had to be thrown out of a window into the snow – because I've long felt that it explained an awful lot about the adult I became.

But looking back I see that this particular childhood experience reveals other truths. The assumption would be that I might have preferred company, but I really wouldn't have done. Snails are an all-consuming business – knowing when to loosen your grip on the spring-loaded tongs takes years of practice – and anybody else would have been a distraction. Plus there is the issue of greed. I wanted to enjoy those snails. I wanted to dive into them, mop up every last bit of garlic butter with every last bit of bread, and if anybody else had been there I would have been shamed into doing otherwise. The solo diner knows no shame, and that's what's so blissful about it. (This may also explain why, from time to time, I have an arse the size of Guildford, but we'll put that to one side.)

Now as a restaurant critic I often eat alone, usually weekday lunches out of London when none of my friends who have proper jobs can join me. I will confess that on these occasions I tend to book a table for two and then announce when I get there that there will just be one diner. This is not out of embarrassment; I don't care whether people think I'm a knobby-no-mates. It's simply that British restaurateurs regard single diners suspiciously, start wondering if we're Michelin inspectors or sociopaths or both, and who needs that?

So I go and I consider the menu and the room. But most of all I study the other people, watch their body language, listen in on their conversations. When I eat alone I have a licence to snoop. Once, in the grand dining room of an Eastbourne hotel, I heard a dignified, elegant couple explaining to their adult children that the space in which we were all eating had long ago been their apartment. "You, darling, were conceived over there," the mother said to one of her sons, pointing at where the cheese trolley loitered, and we all turned to look, as if we might just catch them going at it across the creamy reblochon.

Another time, in a high-class Las Vegas dining room, I was transfixed by the merry dance of a bullet-headed, wardrobe- chested man and his Asiatic "date" for the evening, a woman with glossy newscaster hair and the kind of echoing cleavage in which small children could be hidden. He was demonstrating earnestly how to eat a few hundred bucks' worth of caviar and her responses, hinged between complete disinterest and gales of inappropriate laughter, quickly suggested it wasn't only the food that was expensive that evening. Dinner and a show: who could want for more?

Sometimes I take a book and lose myself in the rhythm of the food and the words and the wine. Downing a bottle at home on the sofa by yourself is, if not exactly sad, hardly glamorous. Doing the same over an impeccable côte de boeuf and crème brûlée with a slab of Philip Roth or Stieg Larsson for company has about it the authentic whiff of adulthood. It says: I am a grown-up. I have taste. I like myself. Now piss off and leave me in peace.

On other occasions I do without the distractions of book or magazine. Those occasions are invariably at the most ambitious of restaurants, where the single diner is regarded with an uncommon respect. I have eaten alone at the Michelin three-star Pierre Gagnaire in Paris and the two-star Noma in Copenhagen and Gordon Ramsay in Dubai. These are places that take what they do extraordinarily seriously, and the assumption always is that if you are eating alone then you take it seriously too. The classier the restaurant, the better they are at entertaining the single diner.

In short, it's an experience for the fully paid-up, got-the-certificate, bought-the-baseball-hat food nerd: I am capable of having long conversations with waiters about exactly which fjord the raw freshwater shrimp I am eating came from; in which direction the wind was blowing when the seaweed that accompanies it was harvested. I have discussed the temperature of the water bath in which the pork belly was cooked under vacuum and what proportion of agar to animal gelatine was used to create the hot savoury sea urchin-flavoured jelly. Bizarre? Look, we're consenting adults and if this is how we wish to spend our time it's nobody else's business.

I do recognise, however, that all of this may obscure, rather than point up, the exquisite joys of eating alone. Happily there is a growing trend in Britain for a type of eating experience which offers the possibility of what we might like to call solo-eating lite – and that's dining at the bar.

Everywhere from Richard Corrigan's Bentley's to Rowley Leigh's Le Café Anglais, from tapas places like Tierra Brindisa in Soho to the sublime, nose-bleedingly expensive sushi joys of Mayfair's Umu or the French fancies of Joël Robuchon's L'Atelier have counters where you can sit elbow to elbow with a bunch of complete strangers and eat.

The self-conscious can take comfort from the fact that at a bar no one can actually tell whether you are alone or not. Plus there is always the staff on the other side to interact with if you get really lonely. Go on. Give it a try. After all, if you don't, the only person you will be depriving is yourself.

Jay Rayner's four best places to eat solo

WILLIAMS & BROWN 48 Harbour Street, Whitstable, Kent, 01277 273373

Sit at the bar at the back of this small but perfectly formed tapas bar serving impeccable jamón Serrano, chorizo baked in red wine and honeyed chicken. As befits a seaside town, the fish is particularly good.

CORRIGAN'S 28 Upper Grosvenor Street, London W1, 020 7499 9943

Richard Corrigan did the solo diner a brilliant service with the seafood bar at his fish restaurant, Bentley's, in Swallow Street, and does it again here at his relaxed but seriously impressive Mayfair outfit. The braised pork cheeks are a particular indulgence, especially when eaten alone.

BOB BOB RICARD 1 Upper James Street, London W1, 020 3145 1000

What more could the solo diner want than a booth all to themselves? This restaurant is ludicrous – it looks like the inside of an Edwardian dining car – but the kitchen really knows what it's doing. A good place for breakfast – they even bring you your own toaster.

PIAZZA BY ANTHONY Corn Exchange, Leeds, 0113 247 0995

There is something about the open design of this space that forces this to be a laid-back experience. So slip on to one of the curvy banquettes and plunder the buttery pleasures that come out of the extremely good patisserie and bakery here. JAY RAYNER

DAISY GARNETT

on trying to avoid biscuits for lunch

Because I work at home, I eat alone at lunchtime most days. Today, for example, in my kitchen is almost an entire leg of an acorn-fed jamón Iberico sitting on its stand, a knife beside it, ready to be carved into – a generous Christmas present from a friend who lives in Spain. Next to the ham is a bread bin and inside that is half a loaf of crusty white bread I made – yes, baked myself – yesterday morning. Why did I bake the bread? Because late on Saturday night I realised my family and I would want a light lunch the next day (we'd had roast chicken that evening) that I had neglected to plan or shop for. Rooting around in the fridge, I found some good bacon but little else, and so I put yeast and salt and flour and water in a bowl overnight so that come morning I could whip up a loaf for our lunchtime bacon and lettuce sandwiches. I almost made mayonnaise, too, but decided that the chutney I had bottled in September from tomatoes I'd grown over the summer would be more delicious. Not a bad effort, given that we'd decided not really to do lunch that day.

So what have I eaten for lunch today? I haven't. Instead, at noon, because I was hungry and didn't want to write a word, I wandered into the kitchen and decided to eat something. And because I noticed it was noon, I decided that I could also read the paper while I ate and justify my snacking as an early lunch. Only because it wasn't actually lunchtime it seemed that a snack, or many of them, instead, would do fine. And so I ate five or maybe seven stale digestive biscuits, an orange, and half a large bar of cooking chocolate. So much easier than carving a piece of ham and cutting a slice of bread, after all. Or what? More delicious? More nutritious? More satisfying?

No. None of those things – obviously. Nor is the problem an issue of effort (I delay work for far less), or knowing what tastes good (I wrote a book about that). No, the problem is eating alone. The problem is tied up with all kinds of things, some of them complex (the usual self-loathing bollocks), and others simple and base (laziness). Because I've worked as a freelance journalist on and off for 10 years, I have eaten by myself hundreds of times, and long ago tried to solve the problem of How To Eat Alone And Enjoy It. Mostly by now I don't snaffle down dry biscuits, a stolen hunk of cheese or a furtive slice of left-over cake. Mostly by now I have taught myself various ploys for eating well by myself. Because rationally, I would advocate nothing less. Eating sensibly and well when alone is a mark of self-respect. It is a mark of respect for food. It is civilised. It is grown-up. It makes sense. It feels good. And it's easy enough.

Mostly, here is what I do. About once or twice a week I walk about a mile to a very good and reasonably priced deli and eat a bowl of their mostly vegetarian, always delicious soup, along with a slice of sourdough bread. Then I walk home, running any necessary errands on the way. So I get fresh air, a break from my desk, good nutritional food and some chores done all in one enjoyable swoop. I don't do this every day because it would add up in cost and because sometimes, amazingly, I am on enough of a roll in terms of work that I don't want to take too much of a break.

So for reasons good and bad, most days I eat lunch and, most days, simply and well. I cook a lot in the evenings and the fridge is often ripe with leftovers. I adore leftovers. Cooked broccoli or greens get reheated with rice, sliced ginger, oyster sauce and garlic, or if I am too lazy or busy, just plain old soy sauce. Left-over squash or beetroot is matched with olive oil and parsley or basil, warmed gently and made into a salad with lettuce and toasted pumpkin seeds or pine nuts, some feta cheese and, if they are also lurking in the fridge, some puy lentils or couscous. Left-over cooked potatoes and courgettes go into a frittata. Soup is often there, as are cannellini or borlotti beans or chickpeas. Fruit is perfect for pudding and so is a cup of very hot coffee.

Left-over meat is left to stretch to another full supper, either in a pilaf or soup. Pasta sends me to sleep and anyway gets eaten for supper all too often. Sandwiches are less my cup of tea unless made lovingly by someone else. But bread and cheese with a couple of cornichons or, in summer, a tomato and a few lettuce leaves suits very well if leftovers are sparse. Ham, when it is acorn-fed, comes from a free-range Spanish black-hoofed pig and melts in your mouth, is unusual, but it happens that at the moment we are rich in it.

So why today, and why about one day out of every five, can I not manage to eat well even when the food is on tap? Why, once a week, do I eat biscuits or crackers or a large bar of chocolate or crisps or cheese not off a plate, or left-over pudding? Why? Because I'm alone and because I can. Am I then satisfied? Not really. But that's sort of the point. Sometimes to be left with a bit of longing is no bad thing. Sometimes, when you are alone, it's the only appropriate thing. Because eating alone is simply not always a celebration, however simple. And you know what else? A bad lunch sure spices up supper.