Like all shrines, this one is on a hill, and built into solid rock. Richard Olney saw it first in 1961 on an excursion south from his adoptive home in Paris. Olney, whose French Menu Cookbook was recently judged the best cookbook ever by this magazine, immediately knew he had found his proper place on earth. "The hillside formed a tapestry of the blues and violets of flowering wild thyme," he recalled, "punctuated by bushes of wild rosemary, feathery shoots of wild fennel and the spring growth of oregano and winter savory – the poetry of Provence was in the air and tender tips of wild asparagus, invisible to the profane, were breaking the ground everywhere. I fell in love."

Olney bought the hill and the derelict farmhouse attached to it for £1,000 and moved to the village, Solliès-Toucas in Provence, almost full time. In the next four decades he discovered a way of life here, and a way of eating and drinking, that he exported to America and the world in his indelible books Simple French Food, The French Menu Cookbook and Lulu's Provençal Table. Friends and pilgrims visited and took home with them something of the hillside. Alice Waters, who has run California's most celebrated restaurant, Chez Panisse, for 40 years, came here first in 1975 and is still, when she describes it to me, heady with the memory. "What I found there," she says, "what I got from Richard, was this total conviction that what he was doing was the right thing. And once you had been to the house, you could not argue with it. It was the truth, I had no doubt about that. There was a kind of religious quality in a way, I suppose. Always using what was local, fresh, seasonal. He didn't preach about it. He just let you taste it, and if you knew anything at all about food, then you knew, straightaway you knew. You didn't need converting."

Olney died in Solliès-Toucas in 1999 and his ashes were scattered in the kitchen garden he had made and across the hillside where he foraged for herbs. Fifty friends and family came here to his wake and toasted his memory with vintage jeroboams of La Tâche, perhaps the most distinguished of all burgundies. The house is still kept as it was when he was alive, preserved by his brothers Byron, James and John, and his sisters Elizabeth and Margaret: it is maintained by a family friend named Marc Lanza, who lives here with his wife and two children, and whom Olney first met as a boy, when the writer used to walk to the village every morning to buy fresh milk from the cows that Lanza's mother kept. The house still has the feel of a shrine to the life Olney lived here. After a two-hour drive west along the coast from Nice, you climb up suddenly into these hills, and then steeply up to the house itself, on a vertiginous road that Olney laid, hefting the sacks of cement on his back, and you begin to discover immediately what life here might have been about.

Olney grew up gay in Marathon, Iowa (pop 600) during the Depression and the war. His father, he recalled in his memoir Reflexions, "was a banker and a lawyer; and although he did not trust doctors, medicine was the only other métier that he considered respectable". But Olney wanted to be an artist and he set off for Paris, where he found himself a garret in which he could make portraits and a new life among friends, lovers and acquaintances that included the black American writer and civil rights pioneer James Baldwin, WH Auden and, distantly, Edith Piaf, whom he saw sing Je ne Regrette Rien for the first time at the Olympia theatre. Olney shared the sentiment. Paris gave him a freedom to live as he wanted, and that sense of possibility he brought not only to his art but, increasingly, into his kitchen. He painted a rough map of the vineyards of France on one wall of his rented apartment, and never looked back.

As a writer, Olney discovered a talent for using words to establish the method and flavour of almost anything, but if pressed for his most singular vocation, you might say that he learned to write about stew better than any man who ever lived. This is him, in Simple French Food:

"Stews form the philosophical cornerstone of French family cooking: they embody – or spark – something akin to an ancestral or racial memory of farmhouse kitchens – of rustic tables laid by mothers, grandmothers or old retainers.

"Les petits plats qui mijotent au coin du feu is a phrase that is used like a word, and it rarely fails to garnish a conversation about food… It means 'slow cooking stews' but it symbolises 'the good life' and somewhere, shadow-like, behind its words lies a half-remembered state of voluptuous, total wellbeing ('Là, tout n'est qu'ordre et beauté, luxe, calme et volupté')."

It was a stew that first gained Olney entry to this good life. He cooked it in his attic flat for a friend, an editor for the gourmands' bible Cuisine et Vins de France. The stew began as an oxtail pot-au-feu from which he discarded the vegetables and bouquet garni and set aside the meat. The broth he used for a beef shank, adding baby vegetables and bundles of leek, celery, fresh thyme and bay leaf and gently heating it for the longest time. His friend declared it the best pot-au-feu he had ever tasted and wrote as much in his magazine. The pot-au-feu became Olney's calling card, granting him entry to some of the most august kitchens in Paris and leading to a revolutionary column in Cuisine et Vins de France: "Un Americain (Gourmand) à Paris: le Menu de Richard Olney". The column ran for a decade, and Olney used it to build an expatriate knowledge of all that was best in French food and wine, rivalled only by his ally and sparring partner Elizabeth David (when they first met, in London, she ridiculed his American pronunciation of "basil"; he scoffed at her taste for an ice cube in her white wine; they became firm friends).

It is a stew, appropriately enough, that greets me when I arrive at Solliès-Toucas in search of the spirit of Richard Olney. Marc Lanza has been cooking all morning a Provençal daube, in one of Olney's favourite red-wine reductions, and its rich flavour fills the farmhouse kitchen that has been preserved just as Olney created it.

Above the enormous fireplace his copper pans of all possible sizes still hang in readiness; his paintings of brothers and friends (and of artichokes and tomatoes) are crowded on the walls; there is a barrel of vinegar, made from the dregs of favourite wines, that Olney insisted should be a staple of any kitchen, and a bookcase filled with editions of Olney's landmark books. Your eye goes first, though, to the middle of the room and a pillar that is papered with wine labels.

As memorials go, this pillar couldn't be bettered. If Olney's restless passion was for food, his abiding love was for wine. His books include the definitive guide to Château d'Yquem, the greatest of sauternes. He always understood wine as a drinker rather than an academic, however, and to prove the point the labels on the kitchen pillar are pasted haphazardly, as if each has been slapped on at the end of a long and tremendous evening: a Château Latour 1963 overlaps a La Tâche 1954, a Château Margaux 1934 vies for space with a Mouton Rothschild 1878. The doors to the house are fashioned from old wooden wine crates; to reach the terrace you pass through a fringed screen of corks; the table is set under a Château d'Yquem vine, and it is here that Marc Lanza serves lunch: a fresh herb salad, with the trademark vinaigrette, and the dark daube, accompanied by the Bandol wine of Domaine Tempier, the neighbouring vineyard that Olney helped to make famous.

While we eat, Lanza recalls his first meeting with Olney, when he was 10. He knew him as the mysterious American on the hill, but the delight he took in collecting the fresh milk was clear. "He struck me straightaway," Lanza says, "as someone who knew how to live." When Lanza was 25 he came up to the house and asked Olney if he might stay in the garden chalet in return for working in the gardens and assisting in the kitchen. Richard was becoming ill with the heart problem that killed him, but he had enough help at the time and there was nothing for Lanza to do. Three months later, though, Lanza received a call from Richard's brothers, telling him of Richard's death and asking if he might consider taking on the house and keeping it alive, as Richard would have wanted.

Like everyone I speak to who knew Olney, Lanza describes his character as "très fort", like the beef daube we are eating. He relished the privacy he was afforded here in an almost monastic way, but he was also a great party giver and host. The simple chalet where I am staying the night was home at various times to house guests including Elizabeth David and the writer Sybille Bedford, and to James Baldwin (Richard's "petit-ami"), his soulmate and sometime romance; a perfect little trio of portraits of the author of The Fire Next Time, asleep and contemplating the world over coffee, are grouped on one wall. A devotee of strong and clean tastes, Olney was a perfectionist in everything and never afraid of a challenge. The last time the Observer wrote about him, in 1979, when he was working as consultant of the Time-Life cookery series, he surprised the writer Paul Levy by boning a whole suckling pig and mummifying it in chaud-froid sauce, in a bathtub in a London flat. There was nothing he could not do. "He had 3,000 cookery books," Lanza says, "and he knew them all." Even to the French his palate was a thing of wonder. "He could smoke Gauloises and still understand all the complexities of the wine." On one occasion, Lanza says, a shipwreck was discovered off Toulon with ancient cases of wine preserved on board, unlabelled. Olney was the man they called for to identify them.

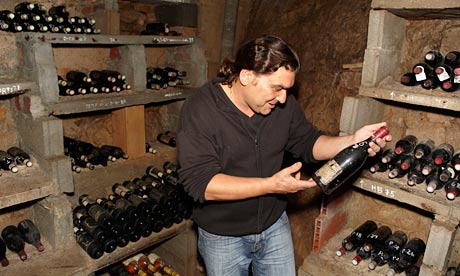

It was always Olney's contention that wine was not for collecting, but for drinking. The Olney cellar is reached through a wooden door that apparently leads to a secret chamber in the face of the rock wall that abuts the house. It has a prehistoric, mausoleum kind of quality, its entrance marked with a ghost tree of empty bottles. Alice Waters recalls him fondly emerging ever more precariously from the depths of these cellar steps, and the unlit cave, with ever more magical bottles to taste, as summer lunches drifted on. That spirit survives. At one point, as the sun declines, I ask Lanza if I might have a glass of water. He looks heavenward in prayer: "Pardon, Richard; they know not what they do."

After lunch we take a walk up on the terraces above Olney's house, which look out across the valley and the village to the hills opposite: an instant Cézanne of roofs and olive groves and planes of light. There is a natural swimming pool set into the rock wall, and a spring which flows down its side. The hill itself boasts eight native orchids and is scented with wild basil and oregano and thyme. The terraces were laid by PoWs in the 18th century. Olney did not drive, so he cooked little that he could not walk to fetch. He bought his olive oil from Mme Gerfroit, "la grande dame du pays" who could identify the village from which an oil came just by tasting it. In Reflexions, the memoir left incomplete at his death, Olney wrote of a world that has all but disappeared but that once was in easy reach of the hill, in which all of Provence's produce was at hand in village shops and not supermarkets ("There are," Lanza tells me, "15 McDonald's now between here and Toulon"). The proximity and freshness of the life Olney knew was celebrated in the carnival atmosphere of dinners on the terrace lighted by strings of coloured bulbs, presided over by the great toad Victor, who noisily descended the steps at dusk to observe the terrace activity.

Looking down on the house from up here after a long lunch, it is easy to conjure Olney's friends ascending the hill for those "simple dinners" – "Chicken split down the back, flattened, skin loosened, stuffed between skin and flesh with a buttered mushroom puree mixture, rubbed with herbs and olive oil and grilled over hot coals" followed by "dried figs stewed in fresh thyme, red wine and honey" and returning down the track – in Olney's words (he was not plagued by false modesty) – "in a vapour of ecstasy".

If Olney discovered the roots of this philosophy in one person, then that person was Lulu Peyraud, who inspired his most cultish book, Lulu's Provençal Table. As Lanza says: "Richard loved the fact that if Lulu wanted a fish she would go to the fisherman; if she wanted a courgette she would go to the garden." With her late husband Lucien, Lulu was and is the life force behind the Domaine Tempier wine that Olney adored; after a night under the cool gaze of James Baldwin, I visit Lulu at her vineyard.

Lulu Peyraud is 93. She has seven children, 14 grandchildren and 24 great-grandchildren. In the summer she still swims every morning in the Mediterranean. ("It is a good arrangement," she tells me with a conspiratorial wink. "My housekeeper takes me down there in the car, and when she comes to pick me up a couple of hours later, she has cleaned the house.") She sits under the vast pine tree in front of the blue-shuttered farmhouse in which she has lived for 75 years and tells me a little about her life, and the vineyard which has been in her family for seven generations.

She first came to live here before the war when she married Lucien, who took over the running of the Domaine from her father. She was, she says, 18 and unable to boil an egg. She learned fast out of necessity. "I had three children very quickly, and a husband who loved food as much as he loved wine, and who was working all day." She experimented with whatever was in season. She grew up eating a lot of vegetables, and that surprised those villagers who – "like Americans" – thought food was "meat and more meat". ("That's why they look so old and I look so young," she says with a smile.) During the Occupation they lived here without electricity or running water and "another baby almost every year". The Nazis were in the next village, but her father, who spoke good German, persuaded them there was nothing for them at the Domaine. While her husband maintained a grape harvest, Lulu grew, and foraged for, leaves and vegetables and herbs.

By the time she met Richard in the 1960s at a dinner in Paris and realised they were neighbours, she had become a famed local cook and hostess. She invited him into their world; Lucien helped to educate him in wine, and she shared some of the secrets of her cooking in generous lunches and dinners overlooking the rows of vines. It was exactly the marriage of food and wine – and life – that Olney had been restless for. "To us," she says, "and to Richard also, that marriage was completely natural; it grew from the same soil – you wouldn't ever think of one without the other, you would never separate them."

Olney brought Elizabeth David here, and Alice Waters. Waters felt, she recalls, as if she had stepped into a Marcel Pagnol film. Pagnol had been the inspiration for Chez Panisse, which takes its name from one of the director's characters. It was watching his films that had made Waters want to try to evoke in California "the sunny good feelings of another world that contained so much that was incomplete or missing in our own – the simple, wholesome, good food of Provence, the atmosphere of tolerant camaraderie and great lifelong friendships, and a respect for both the old folks and their pleasures and for the young and their passions". At Lulu's table she discovered that life for real. On the first occasion she and Richard visited, after Lulu's lunch they tasted all the new wines in the wood in the Tempier cellars and ended the afternoon dancing the tango until they collapsed on the cellar floor.

It was Waters' idea that Olney should write a book about Lulu's cooking, which he did in 1993. Lulu would go to his kitchen every afternoon "and cook something, and Richard would watch, that is how the book happened. Very simple". Lulu joined him on a bibulous book tour of the States. At 93 she remains something of a pin-up for a certain kind of ardent foodie. Coach parties of Americans make a detour here. Lulu has, she says, suggested to her business manager that when she dies he should have her embalmed in the tasting room so pilgrims can still be pictured alongside her.

Alice Waters still makes the journey down here when she is in Europe. When I speak to her in California, she is preparing to celebrate 40 years of Chez Panisse with 40 menus dedicated to people who inspired a revolution – of slow food and seasonality – in the best American cooking. First on the list is Richard Olney. She has been impressing on her chefs that "Richard was always more about living a life than running a kitchen. That it was an agricultural way of living, with a profound emphasis on the culture." And Lulu was central to that culture. "They complemented each other perfectly. Lulu was open about everything, and that was important for Richard: he was a very private person, he didn't find it always easy to be the host – but Lulu opened her family to him and he became part of that family, which was crucial to him…"

What are her most vivid memories of him?

"You would always want to watch him just putting a leaf on a plate. You could never argue with his salads. He did it all with such care. It is an unusual skill to be able to paint, and to be able to cook, but you could say it came from the same place. At those lunches I was always on the edge of my chair for what came next."

It is that excitement that she has imported back to the States, where, as in Britain, with champions such as Simon Hopkinson, Olney's reputation and influence continue to grow.

"It is a shame he did not live to see it happen," says Waters. "I mean, he worked so hard at his books, and though they sold in his lifetime he would like them to have done better. What he longed for was to sell enough books to allow him just to paint, and to live as simply and perfectly as he wanted." Richard Olney may never quite have got to that point, but you can't help feeling that he got a good deal closer than most.

With thanks to the Olney family.