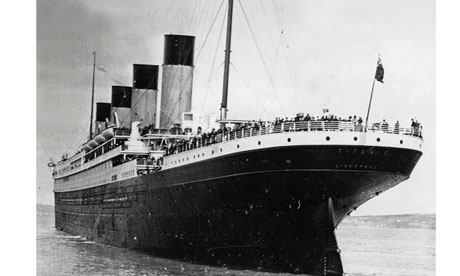

No doubt it says something rather sick about me that when a friend mentioned it was possible to buy a book of recipes from the kitchens of the Titanic, I felt, for the very first time, a stirring of interest in the doomed liner. In the past, I've never quite "got" the Titanic. Last summer, I travelled to Hungary to see the set for Julian Fellowes's forthcoming series about the ship (the drama will mark the 100th anniversary of its sinking, which falls next year). But even faced with a vast replica, I found myself wondering why it is this particular disaster that resonates. Is it the cold mass of the iceberg, or the fact that the band played on? Is it the absence of sufficient lifeboats, or the sheer numbers of dead? The last of these, I would guess – though I do see that, given my new found interest in what these poor souls ate by way of a last meal, I'm not in much of a position to be judgmental.

Anyway, soon after, I bought a Titanic cookbook of my own: Last Dinner on the Titanic by Rick Archbold and Dana McCauley (I passed on RMS Titanic: Dinner is Served by Yvonne Hume, the great-niece of the ship's first violinist; that subtitle is a bit too disturbingly cheery even for me). It makes for a strange read, and not only because it ends with instructions on recreating your very own "night to remember" at home, including how to build the right atmosphere (men should stand whenever a woman enters), how to fold your napkins (the Bishop's Mitre is recommended), and what to talk about (spiritualism was then much in vogue, so why not invent your very own spirit guide?). It's more the tone of the thing that's off. As the authors note, how unfortunate that none of the surviving passengers who ate in the à la carte restaurant on the night of 14 April, 1912, thought to tuck a menu into the pocket of their jacket!

Two menus do survive, however, of which the most fascinating is the one from the first-class dining saloon (the other is a second-class menu, and it sounds like high table at a posh university). How greedy the rich were then – so different from now, when to be wealthier than anyone else is also usually to be thinner. Guests in first class – among them John Jacob Astor and Benjamin Guggenheim, neither of whom survived – ate a menu that consisted of 11 rich courses. The book includes recipes for all of them, though the authors urge caution. "Do not try to prepare this menu yourself," they say, in their handy three-day planning guide. "Enlist at least one sous chef."

The dinner began with canapés a l'amiral, an Escoffier standard consisting of toast and shrimp butter. There were also oysters. After this, there was a choice of soup: consommé Olga – a broth flavoured with the dried spinal marrow of a sturgeon – or cream of barley. Course three was poached salmon with mousseline sauce, and course four, a choice of filets mignons or chicken Lyonnaise. After this: a roast. Choose from lamb, duckling or beef. By now, guests were probably reaching for the Gregory's Powder (a "stomach sedative" made, I think, from rhubarb). So course six was an alcoholic sorbet, punch Romaine. Refreshed, diners then ate roasted squab, followed by asparagus, followed by pâté de foie gras. Finally, there was pudding – peaches in chartreuse jelly or chocolate eclairs – and fruit, cheese and coffee.

The book's foreword was written, five years before his death in 2002, by Walter Lord, author of the classic 1955 account of the sinking of the Titanic, A Night to Remember (Penguin will reissue it next year). In it, he writes that a surprisingly high number of "sentimentalists" sit down to a special dinner every 14 April. Can this be true? I don't know. I briefly toyed with the idea of doing a Titanic dinner myself, but it seems a bit naff, like staying in one of those hotels where everyone pretends they're in an episode of Poirot. One course, on the other hand, would make for a perfectly tasteful tribute – and so, next year, I plan to serve another first-class treat, punch rosé, to any landlubbers who happen to be in the vicinity. Here's how. First make a syrup by dissolving approximately 90g sugar in 60ml warm water. Boil for a minute. In a food processor, mix this with 375ml rose water, 250ml water, a handful of mint leaves, and a teaspoon of lemon juice. Blend until the mint is finely chopped. Freeze in an ice cream maker, and serve in champagne dishes. Absolutely no aspic or plover's eggs required.