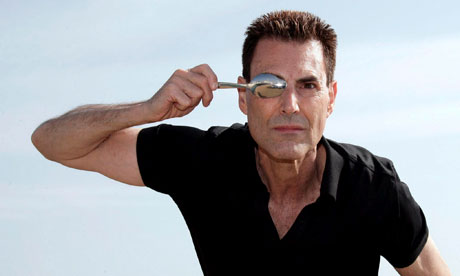

When I visited him, in 1996, the world's most famous cutlery-bender popped into one of his Berkshire mansion's two kitchens – one for him, one for his mother – to find a spoon to reshape for me. Then he took me to see his Cadillac, on to which thousands of spoons had been riveted. Spoons, so rich in symbolism, had become "like a business card". But he said, "I'm getting fed up with spoons", and the double meaning made me keen to talk about his relationship with food.

His earliest recollection was from age four. "I was living with my mother in one room of a shabby apartment in Tel Aviv, and I was eating her soup one lunch and, as I lifted the spoon towards my mouth, it started bending, then broke in half." Strangely enough she wasn't amazed. "Having an electrical charge in your body, capable of doing such a thing, would mean you'd be hopping around like a prawn on a hot plate," I argued. "But it's not electricity," he said. "Nobody knows what it is… Have a vegetarian low-calorie cookie."

Uri said that if I drew something, then gazed into his eyes, he would attempt to tell me what I'd drawn. After a good deal of staring, he said: "What I'm getting is a circle." No, I said, and revealed my drawing of a spoon.

He had a dining room which he'd never eaten in. But it was his experience of bulimia which most intrigued. "I fell into a cycle of eating and vomiting – killing myself slowly." Uri found the willpower to end the cycle around 1978, and had since undertaken four hours of punishing exercises per day, which meant he'd consume 5,000 calories ("a lot of pasta") but still be slender. "Fifty miles cycling is moderation, for me."

"Do you like food?" I asked. "I love eating," he said.