Getting on for a decade ago, while working as a recipe tester for a food magazine, the truth was laid out to me. While making dumplings with a colleague, talk had turned to my career hopes: writing cookbooks. "Alice, you do realise there's no money in cookbooks?" I was told. That can't be right, I thought cheerfully. She's clearly doing something wrong.

Initially, I just enjoyed cooking. After A-levels, I begged my way into a restaurant kitchen, but still trooped off to read neuroscience (I like to think a good knowledge of anatomy and dissection has helped me out in the kitchen). At university, I began cooking for local events companies and had to be bribed to complete the degree by my concerned parents who thought it would be better to have a "qualification" to fall back on if the food phase fell through. And the bribe? A helping hand with the deposit for Leith's school of food and wine. For the rest, and it felt like a fortune, I took out a career development loan, paying it back through catering and restaurant jobs. Going to Leith's was one of the better decisions I've made, especially for the in-depth knowledge of how and why a recipe works.

After working as food editor on magazines, I managed to get an agent and wrote my first cookbook in 2010. I've written two more since and, though I love the work, the unglamorous truth is the hours are appalling. I'm constantly surprised at how little time there is. Food shopping, prepping, writing and testing on into the small hours are an all-too-familiar occurrence. It's not something that particularly bothers me; I love the work, but the notion of cookery books being a money-spinner is only true for the big names.

I've also found that food styling (cooking food for photographs) combines beautifully with writing recipes, allowing control freaks like me to be fully involved in a feature or book. We always eat the grub, by the way, and the ice cream is the real thing, not mashed potato as it might have been in the 70s.

Knowledge is power

If you want to write and understand good recipes, first you'll need to work with food, but concentrating on what you do, or love, best. You might be a born pastry chef with a delicate touch, a specialist in Malaysian cuisine, or creative with canapés. Be honest about where your talents lie and be able to prove them, but first equip yourself: you must know what you're doing in the kitchen, starting with how to use a knife properly. Only once you have a solid cooking identity, can you start to build on it.

If you want to write cookbooks, you must read cookbooks

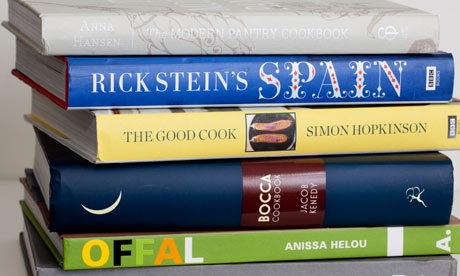

Read all the cookery books you can and develop your own writing style. It will take time and practice; I'm not sure I've perfected my own style just yet. Consider writing a blog: it's a good practice and a way to advertise yourself. These days, a publisher will want to know how they can sell, not just the food, but you the writer. By showing what you're about and who your target audience is, you've just made their lives easier and yourself more hireable.

Test, test and test again

Test your recipes. Twice at the very least. Use proper scales, spoon measures and an oven thermometer. Rake your finished recipe for typos, paying close attention to weights and measures. An editor can mop up errors, but they won't know if that three was meant to be a one (I speak from experience here, having once signed off a magazine recipe with a vastly reduced cooking time; suffice to say there were complaints!). Many publishers don't have book recipes tested; there simply isn't the money to do that with everyone, unless the author is a famous name. It is up to you to make sure they work or you will soon gain a reputation; our climate of instant information, via blogs and Twitter, means news of a badly tested recipe will travel faster than a good one. The trust between you and the reader is easily lost.

Talent borrows, thieves steal

Try not to copy and if you have "borrowed" or faithfully reported, quote your source. It's hard not to take inspiration from other sources, even unwittingly, but have respect for your fellow writers. Of course, recipes are stories and, rightly so, are recorded down through the generations and across continents, just be careful where you are claiming an "original" and always namecheck your sources. Travel. Make notes, eat street food, be nosy; this is where the inspiration lies.

Keep it simple

Think of your intended readers and their kitchens. Are they going to be able to get hold of the ingredients? Will they have the ability, equipment and time to cook the recipe? Will they want to buy your book? Set snobbery aside.

The thin-skinned need not apply

Don't be knocked back by rejection. Perhaps the publisher just couldn't place you or market you because they have a similar book idea or even a similar author already? Go elsewhere and try again, refining your idea if need be. I was turned down first time around. A different proposal was then accepted by the publisher a couple of months later.

Don't expect to get rich

Unless you're already a big name chef or on television, there isn't much cash to be made as a cookery book writer. You will certainly need to add more strings to that culinary bow to pay the bills. But at least there'll be good food in the fridge.

Alice Hart is author of Alice's Cookbook, Vegetarian, and Friends at My Table, all published by Quadrille