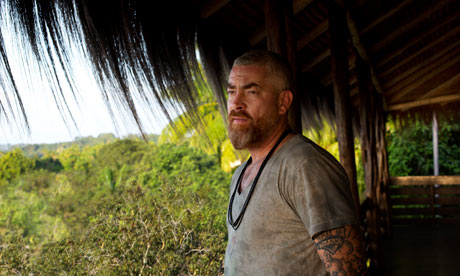

Last month Alex Atala was named one of Time magazine's 100 most influential people in the world for taking on "the enormous task of shaping a better food culture for Latin America. His philosophy of using native Brazilian ingredients in haute cuisine has mesmerized the continent." This week, DOM, his São Paulo restaurant, was voted the sixth-best in the world (down from fourth last year) and the best in South America.

So how did a former punk rocker, DJ and self-confessed party animal who became a chef almost by accident (while bumming around Europe he applied to do a cooking course in Belgium so he could get a visa), and from a country with little reputation on the world food scene, change the way people think about Brazilian food?

Atala says his lightbulb moment came when he realised that, despite training in France and Italy, he would never, as a Brazilian, be able to cook those countries' cuisines (which dominate the fine-dining scene in São Paulo) as well as a native chef. But maybe he could cook Brazilian food better than anyone ever had. As well as having the chutzpah and self-belief, he was blessed by the country's abundance of unique natural ingredients.

Here's the thing about Brazilian food. While the raw materials – meat, fish, fruit, veg – can be as good and as varied as anywhere in the world, almost all the manufactured foods on offer are industrialised and bland – cured meats, dairy, oils, beer … even coffee. They may have an awful lot of coffee in Brazil, but it usually tastes bloody awful, too.

So Atala stopped aping cuisine that relies on imports or poor substitutes, and turned for inspiration to his country's natural resources, in particular to the Amazon. The world's greatest ecosystem is home to a cornucopia of ingredients (and many species of plant still undiscovered), and this is where he stocks his pantry. So on the menu at DOM are some weird and wonderful Amazonian foods. Tucupi is a yellow sauce extracted from a manioc root that must first be boiled to remove the toxins; jambu leaf numbs the lips and tongue and, says Atala, "makes everything taste bigger". There are also some of the world's largest freshwater fish, and an amazing honey which, according to the Brazilian food standards agency at least, isn't honey at all.

I'm sitting in DOM with Atala and he tells me to take a spoonful. It's so good I immediately ask for another dip.

Atala smiles, as if to say I've already proved his point: "I'm serving this illegally, because according to the law this isn't really honey as it doesn't have the required viscosity. It's too liquid. How mad is that? Honey in Brazil is made by bees imported from Europe centuries ago, but we've got our own bees, and guys in the Amazon who produce this amazing stuff – illegally."

That, in a nutshell, is Atala'a quest. Not only to bring Brazil's culinary diversity to the world's attention, but also to help small-scale producers like the guys who make honey in the forest. He is now regarded as an emerging voice in the environmental movement as well as a chef: he works with indigenous communities, showing them how important the ingredients around them can be. "We [Brazilians] are starting to realise that the rainforest is an asset," he says, "but to use it, we must conserve it."

This mission has taken him on a culinary voyage around Brazil, and made DOM a showcase for Brazilian ingredients. (The Latin acronym stands for deo optimo maximo – to god the best and greatest; Atala changed the first word to domus – signifying the home of the best and greatest gastronomy.) "I feel a kind of responsibility to show the amazing diversity of our produce."

When I ask him how many of Brazil's 26 states he sources produce from he doesn't know, but he loves the question: "I've never really counted – but I'd guess all of them!"

So on the menu there are wines and oysters from the temperate south of the country and new strains of rice (one a mini variety that looks a bit like couscous, another black and crunchy) that he has developed with a farmer in São Paulo state. But it's the obscure herbs, fruits, flowers, fish and even insects from the Amazon basin that steal the show. Which is why I find myself looking at a small plate containing two raw unseasoned ants atop a one-inch cube of pineapple.

"It's OK, they are dead," says the waiter. "Eat them with your fingers."

I take a bite and, to my astonishment, get a hit of lemongrass, only more intense, like the essence of lemongrass.

Atala later tells me he discovered the ants on one of his many trips to the Amazon. "I was with the Baniwa tribe in the far north, near the Venezuelan border. Interestingly, they don't eat these ants for protein, the way other cultures often eat insects, but as a treat, a bit like sweets."

It's the most mindblowing dish on a menu that is pure culinary theatre. His "coconut apple", the yellow spongy centre of a germinated coconut, which is not usually eaten, is served with seaweed. I could only describe its taste as like something that has been washed up on a tropical beach. It is paired not with wine but with cachaça, the clear Brazilian sugarcane spirit that rocket-fuels caipirinha. His take on spaghetti carbonara is just as playful, the pasta replaced with crunchy strings of palmito, white fleshy palm hearts, a classic Brazilian ingredient.

As with any restaurant of this quality the prices are as bonkers as some of the food on the tasting menu – but there is also a three-course set lunch for less than £30. And to be fair, some of the ingredients come from such remote parts of the country that Atala spends more money transporting them than on the products.

In the past decade this nova cozinha brasileira has been taken up by other Brazilian chefs, more of them in São Paulo rather than its great rival, Rio de Janeiro. São Paulo is where the money, and so the innovation, is.

"In São Paulo we work; in Rio they go to the beach" is what everyone says here, but that affords them a vibrant nightlife and restaurant scene that its more glamorous rival can only envy.

A few blocks from DOM but still in the Jardins, the city's swankiest neighbourhood, chef Helena Rizzo and her Spanish husband Daniel Redondo run Maní, which has also entered the list of the world's 50 best restaurants this week, at number 46.

Maní is more rustic and informal than DOM – simple furniture, whitewashed walls and a ceiling of dried branches laid over rafters – but the food is no less adventurous. A signature dish is baked manioca with coconut milk and tucupi froth. There's also a clever interpretation of feijoada, Brazil's national dish, where the "beans" are actually the concentrated essence of the dish, sealed in a bubble of gelatine to look like a bean, and a waldorf salad in which the walnuts are caramelised, the apple is jelly and the celery ice-cream. It might sound pretentious but both are absolutely delicious.

Seeing jabuticaba on the menu brings back happy memories. I came across this purplish-black fruit 20 years ago on my first trip to the country: I found myself up a jabuticaba tree in the backcountry of São Paulo state while, I must admit, stoned out of my own tree. I ate it straight from the branches and had never tasted anything quite so exotic in my life.

But I've never seen it on a menu before. At Maní, this quintessential Brazilian fruit comes in the form of a fuchsia-coloured cold soup with a prawn steamed in cachaça. Like everything I eat at Maní it not only tastes wonderful, it is also beautifully presented, with a light, elegant touch.

Josimar Melo, food critic of daily newspaper Folha de São Paulo, has described this movement as "bossa nova cuisine", comparing it to the late-1950s movement that shook up Brazilian music by mixing a foreign form, jazz, with a native one, samba.

"Today, there's a similar thing happening with Brazilian food," he says . "As with bossa nova, a new generation of chefs is not limited to copying foreign influences; rather they are applying European techniques to Brazilian ingredients."

It's a neat analogy from a man who lectures in the history of cuisine at a São Paulo university. I tell him I am not here just to eat in high-end restaurants; I want to try traditional Paulista food.

Josimar smiles: "There isn't any! São Paulo was little more than a village until the late 19th century, so the history of São Paulo food is really the history of its immigrants."

Migration has turned a sleepy town with a population of 31,000 in 1872 into today's megacity of 21 million, the ninth-biggest city in the world and South America's wealthiest and most important economic hub.

Immigrants from Italy, Portugal, France, Syria, Lebanon and Germany have all shaped the city's culture and cuisine, but what surprises many visitors is that São Paulo is also home to the world's largest Japanese community outside Japan. They started coming in 1907 to work on the booming coffee plantations and there are now more than a million, including the Nikkei, Brazilians of Japanese descent. As a result, sushi is the city's answer to chicken tikka masala – ubiquitous and loved by almost everyone.

Josimar suggests a couple of places that are way out of my price bracket, but says, for a taste of the old Japanese São Paulo, I should try Sushi Yassu in Liberdade, São Paulo's Little Japan. It's on Liberdade's main street which, as with many Chinatowns, has been orientalised with lanterns and Japanese signs, and lots of shops selling imported food and knick-knacks. With its tatami floor, paper screens and peaceful atmosphere, Sushi Yassu feels like a slice of old Japan in a city heading full pelt into the modern world. And the combination plate of sushi, sashimi and tempura served on a wooden board, is good value.

Around the corner is Lamen Aska (Galvao Bueno, 466), another of the city's last old-school ramen houses, this one serving big bowls of delicious miso soup for under a fiver and a plateful of gyozas (meat-filled dumplings) for even less.

I finish the night at Choperia Liberdade (Rua da Glória 523), a fabulously kitsch Japanese karaoke house, illuminated by Chinese lanterns and tropical fish tanks. I popped in for a nightcap but end up staying for two hours, serenaded by locals murdering everything from Japanese power ballads to cheesy Brazilian pop and Bohemian Rhapsody. If you're in São Paulo to party, don't miss this place.

Choperia Liberdade typifies the multiculturalism that Paulistanas (natives of the city) are justifiably proud of, but this isn't a modern melting pot like London or New York. Mass immigration into Brazil practically stopped in the early 1960s, so the majority of young Brazilians are at least third-generation. Since the war, the migration has been internal, with millions heading from the impoverished north-east to the south to work as maids and in factories.

(The most famous migrant is Luiz Inácio "Lula" da Silva, who as a seven-year-old made the 13 day-journey from the state of Pernambuco to São Paulo on the back of truck. Half a century later, he would become the country's first working-class president and a political superstar).

Nordestinos brought their hearty, meaty peasant cuisine with them, and one former factory worker, Jose Oliveira de Almeid, called simply Seu Ze, opened a small restaurant called Mocotó in the working-class suburb of Villa Medeiros. Forty years later, the restaurant and its young chef, Rodrigo, Seu Ze's son, are the talk of the São Paulo food scene.

Traffic in São Paulo is hell and Mocotó is 10 miles from the city centre but on the way to the airport, so I make it my last stop. At weekends the city's upper and middle classes make the same traffic-congested journey and wait for up to three hours for a table at the simple but buzzing restaurant.

Mocotó is stewed cow's foot, and the very thought of that had always put me off. But, at this eponymous restaurant at least, it's as delicious as it sounds repulsive – a rich, sweet broth packed with meaty flavours. Other specialities are baião de dois (black-eyed peas, rice and soft cheese), carne de sol (sun-cured beef), and torresmo (pork scratchings). Hailing from near the Black Country I've eaten my share of scratchings, but never any like these. They are deliciously light and crunchy, but still connected to cubes of tender pork. I later discover that Oliveira imported an oven from Germany so he could cook them just so.

Mocotó is also a cachaçaria, selling more than 500 cachaças – a tipple often associated with poor people and drunks – from all over the country.

Opening directly onto a ramshackle street and selling food the majority of Brazilians can afford, Mocotó is a world away from DOM, but Oliveira is just as serious about food as Atala. So serious, in fact, that he now has a research kitchen upstairs and employs a cordon-bleu French chef to help develop the menu – a bit like a young Raymond Blanc working in a fancy East End pie and mash shop.

Just before I leave for the airport, Seu Ze, still on hand behind the bar, makes me sample a few cachaças to help me "relax" on the flight. I leave happy, and not just because I'm full of pinga, as the firewater is known. This new Brazilian cuisine is still in its infancy but I've been convinced they've really got something going.

• Flights were provided by British Airways (0844 493 0787, ba.com); direct flights from Heathrow to São Paulo start at £724 return. Accommodation was provided by Only Apartments (only-apartments.com); the São Paulo Jewel apartment in the centre of the city (it's a good idea to stay centrally given the traffic) sleeps five and costs from £214 a night. Other apartments sleeping up to four cost from around £94 a night

Alex Atala's book on Brazilian ingredients will be published by Phaidon in the autumn