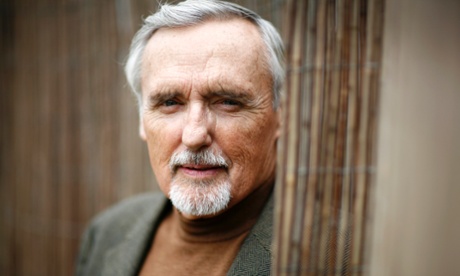

Most people given the opportunity to interview Dennis Hopper were content to know about the effects on his life of James Dean, Marlon Brando, Jack Nicholson, or Natalie Wood. I chose Mao Zedong.

We were talking in Notting Hill in 2004. I was going through a period of being fascinated by people who have damaged art, and more than anything I wanted to hear why Hopper had fired bullets into his Warhol portrait of Mao.

“Why not?” he replied, eyes wide, “I bought, I owned, I shot. I got crazy, I got frightened. Take some water. You like plain, or fizzy?... I never met the guy [Mao], but my father did. When I was a kid, he went on secret ops in China, so Mom told me he was dead. Then he turned up later. I’d forgotten him. Christ reborn.”

Hopper clicked glasses of mineral water with me at this juncture. “Cheers!”

Water and talk of childhood led Hopper to note “I was conceived out of the dust and drought. The dying agriculture of the great plains. Bread lines. Kansas [in the mid-30s] was dry as a nun’s pipe. Blizzards of top soil and wheat. They say it got hot as hell right after I was born. I expect I was thirsty, dehydrated. I got left on my own pretty much at my grandfather’s farm. Some pigs, chickens, cows. I remember blowing dust off plates, off onions. Your head spins if you blow too much. Life on the farm. You can run, play and scream all you want in Kansas. But then what?

“My grandmother would carry 30, 40 eggs to town, in her apron, like this, like she was knocked up, and once she’d sold them I got to go to the movie house. If it wasn’t for those eggs, I’d be... dust.”