Apart from a bottle of apple-scented shampoo and a jar of piccalilli I once picked up in a particularly rubbish school tombola, which obviously don’t count, I never, ever win raffles. So when I added my name to the ballot for a table in the revolving restaurant on the 34th floor of the BT Tower, which will celebrate its 50th birthday by re-opening for two weeks this summer, I felt only the tiniest flicker of hope. Would I be one of the 1,400 lucky diners? No, I most definitely would not.

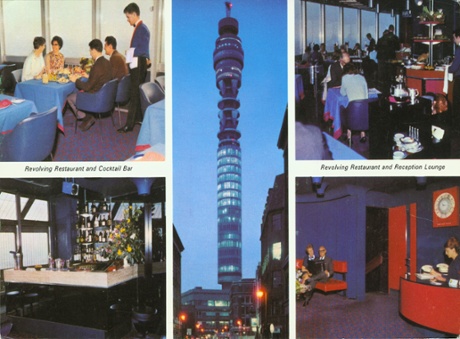

All the same, it had to be done. That sliver of anticipation was enough. I’ve fantasised about eating in the restaurant of the BT Tower for most of my life, which seems rather amazing considering that when it finally closed to the public in 1980 I was only 11 and my first visit to London was still some years in the future. But I knew all about it even as a child: the fact that its famous dining room made one revolution every 22 minutes; that it was operated by Billy Butlin; that the menu included such delights as chicken kiev and scampi; that the tower itself was an official secret, and therefore appeared on no Ordnance Survey map for all that it was 191 metres high and built of concrete and steel. What, I used to wonder, was a mere Berni Inn beside this epicentre of sophistication and glamour? It was nothing, that’s what, and all the Irish coffees in the world wouldn’t ever change that.

I suppose I was quite a weird kid. But perhaps I was also just beginning as I meant to carry on. I have a thing for “lost” restaurants: a peculiar almost-nostalgia for tables at which I will never sit, napery I will never use, dishes I will never taste. A few of these restaurants, gone but not (by me) forgotten, were around in my adulthood, but at a point when I was too broke ever to eat at them, the most obvious and painful example being the remote Altnaharrie Inn at Ullapool, once the only restaurant in Scotland with two Michelin stars (I used to make a colleague who’d travelled by boat to spend his wedding night there describe it to me over and over again). Most, though, shut up shop long before I was born. I know of their existence only thanks to the books in which they sometimes appear, conjuring in a moment the sudden clatter of lunchtime silver: La Terrazza in Soho; Alvaro’s on the King’s Road in Chelsea; The White Tower in Fitzrovia; Robert Carrier’s little place on Camden Passage in Islington; all the various Lyons Corner Houses.

Restaurants are peculiarly evocative: read even the briefest description in a diary or memoir of a supper out – “we had the oeufs en gelee followed by the Dover sole… nice bottle of Muscadet… Tynan was in a corner lunching with some moon-eyed young starlet” – and it’s like time travel: you’re there in an instant, smoothing down your shantung shift, flipping open your cigarette case, patting your back-combed hair. Even more immediate is London Dossier, edited by Len Deighton in 1967 and billed as insider’s guide to the “most exciting City in the world” – an inspired gift to me from my beloved. Thanks to this Penguin paperback – its cover has a keyhole cut into it behind which there lurks a close-up of Twiggy – I know that the best 24-hour restaurant in the capital was once the West London Air Terminal (serving the future Heathrow Airport, this building was bizarrely to be found in Kensington); that even in 1967 people worried about the loss of the “fine old pie shops” like Joyce’s near Tower Bridge, with its pew seats and zinc counter; that the then king of seafood was Tubby Isaacs who operated one of his many stalls in Goulston Street, Whitechapel; that Nick’s Diner in SW10 offered a full delivery service – salmon profiteroles, lamb Provencal – providing it had at least 24 hours’ notice.

Human beings are programmed for wistfulness and remembrance; a yearning for what one cannot have is hardly an uncommon thing. Nevertheless, I’m not aware of too many other people who know, as I do, that the old telephone number for Trattoria Terrazza, whose regular clientele once included Julie Christie, Terence Stamp, Leslie Caron and David Niven, was GER 8991. And thanks to this, perhaps my inevitable failure in the BT ballot – I can already feel it heading my way, like a really bad cup of coffee – can only be a good thing in the end. The view must be amazing. But little else about it will ever be able to live up to my unnervingly vivid almost-memories.