Dig up your lawn and plant your flowerbeds with spuds. Marry a farmer. Buy land. The United Nations, commodity brokers and hedge funds, banks and governments all seem to agree that high food prices are here to stay.

According to mySupermarket and other food price-tracking sites, a typical shopping basket in Britain now costs around 6% more than it did last year but specific foods and key staples are clearly much dearer. Some English butter is up 40% in a year, chocolate biscuits 50%, coffee 20% and pasta 29%.

Meanwhile, on the back of droughts and floods, oil price rises, speculation by hedge funds and increased consumer demand from China, the price of many staple foods is rising faster than it has for two years, and is now close to the records set in 2008/9 when the oil price peaked and food riots broke out in 26 countries. Wheat, maize, sugar and coffee have hit near record levels in the last six months, and dairy, oils and cereal are all 20-50% above where they were last year. In the last six months, too, many leading food companies have said they expect commodity prices to rise at well over the inflation rate this year. Unilever expects a 14-16% increase, Nestlé 8-10%.

British food prices are rising faster than in other rich countries, says Paul Donovan, deputy head of global economics at UBS, the biggest Swiss bank, because supermarkets, which control 80% of Britain's food sales, have taken advantage of commodity prices and consumers becoming accustomed to inflation to drive prices up. Only 20-25% of the price of any processed food in a country like Britain – such as a loaf of bread, or a packet of chocolate biscuits – is directly due to the global commodity price, he says, whereas 70% or more of it is down to "labour" costs – which include packaging, marketing and distribution.

Theoretically, if commodity prices rise worldwide, they should have little effect on what we pay in shops. In fact, says Donovan, in a paper published this year, UK food prices are rising at nearly double the level in the United States and the euro zone or any other rich country.

"A convincing case can be made that these food price increases exceed those justified by cost increases," he says. A spokesman for the British Retail Consortium, which represents all supermarkets, says the situation is "the absolute opposite" and that the full cost of commodity price inflation is not being passed on to consumers because "retailers are engaged in a fierce battle between themselves to keep prices down".

Globally, the UN also sees food prices rising over the next 10 years as higher energy and fertiliser costs affect farmers. In a recent report, the UN said it expected cereal prices to be 20% higher on average, compared with the previous decade, while meat prices would be up to 30% higher.

Inevitably this will hit the poorest the most. In Britain, families spend around 15% of their budget on food. In developing countries, this rises to 50% or more. In Lusaka, Zambia, where the Jesuit Centre for Theological Reflection in Lusaka, Zambia has tracked food prices since 1991, many staples are at historically high levels, having risen 50-75% since 2006. The World Bank said last month that 44 million extra people have been forced into extreme poverty since last June by food inflation. Lester Brown, head of the Washington-based Earth Policy Institute, sees demand rising as the world population grows by 89 million a year and political unrest increases. "Historically, price spikes tended to be almost exclusively due to bad weather, but today, they are driven by both increasing demand and decreasing ability to supply. With a rapidly expanding global population demanding to be fed, crop-withering temperatures and exhausted aquifers are making it difficult to increase production," he says.

"Until recently, sudden price surges didn't matter as much, as they were followed by a return to the relatively low food prices that shaped the political stability of the late 20th century across much of the globe. But now both the causes and consequences are ominously different. Get ready, farmers and foreign ministers alike, for a new era in which world food scarcity increasingly shapes global politics."

Britain is sensitive to world commodity price shocks because we import nearly all our fruit, half our vegetables and much of the other commodities we eat. Government has argued strongly that it expects food prices to remain low and that cheap imports and the global trading system will best serve people's needs. But as the era of cheap food ends, so the need to rethink our supplies becomes urgent.

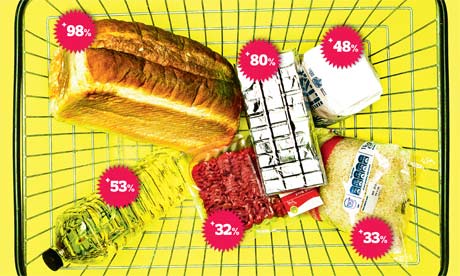

Commodity price rises 2010-2011

WHEAT + 98%

A searingly hot summer in 2010 devastated wheat and cereal crops across 2m square kilometres of Russia, Ukraine and Kazakhstan last year, sending world prices to twice what they were in 2008. This year, France and Germany, Europe's biggest cereal exporters, expect yields to be 15-20% down after the driest spring in nearly 100 years, adding to inflationary pressures.

But because the wheat in a loaf of bread represents only around 10% of its cost in rich countries – the rest being energy, packaging, transport and shop costs – even the doubling of the commodity price in a year should only justify a small rise in the shop price of bread. Instead, supermarkets and the food industry have raised prices by as much as 25%.

For most of the world, though, a series of major droughts in Australia, the US and Europe has led to increased hardship and shortages. In Lusaka, Zambia, where the commodity rise is reflected in the price that consumers pay, the cost of a loaf increased 75% from September 2010 to April this year.

The Food and Agriculture Organisation in Rome suggests upward pressure on cereal prices will continue, if only because not much more will be planted. This is partly because the US and Europe are switching hundreds of thousands of acres of land from food production to biofuels. According to the US department of agriculture, nearly 44% of US corn is now processed for fuel.

The key factor in many cereal prices is oil. Turmoil in oil-producing countries has pushed crude above $120 a barrel, which is expected to drive wheat and maize prices even higher. Higher crude prices make biofuels produced from crops more competitive while raising the cost of tractor fuel and fertiliser.

BEEF + 32%

The price of beef, and most meat such as chicken, lamb, pork and duck, depends on the price of the food that is fed to the animals. Nearly half the UK harvest is fed to livestock and 60% of the price of most beef is now in the feed.

This makes meat prices extremely sensitive to weather extremes and speculation in grain future markets. In the past year, global grain harvests have been devastated by drought, heatwave, abnormal rains and flash floods producing record feed prices.

But beef is especially expensive. Far fewer cattle are being reared after years of drought in Australia, the US and Europe. In Britain, where feed prices rose 25% in a few months last year, and beef and lamb are now at almost record prices, a weak pound has made it more profitable for farmers to export, and more expensive to import.

According to the US department of agriculture, global beef production is declining because cattle farmers have been reducing the size of their herds to compensate for a major US drought, record feed prices and squeezed profits.

SUGAR + 48%

Eighteen months ago sugar was the "new oil" as commodity dealers in New York speculated on the possibility of an international shortage. The price, which for years never rose much above 12 cents per pound, more than doubled in less than 12 months and last year hit a 30-year high, from which it is not expected to fall much. A growing sweet tooth in China and other developing countries, plus a succession of bad harvests and extreme weather in places including Australia and Brazil, suggest the international price will indeed remain high.

But the price of sugar is determined by more than just weather and speculators. Because ethanol can be derived from it, to make vehicle fuel, the sugar price more or less tracks energy prices. When oil spiralled in 2008, so did sugar. In addition, many governments subsidise the price and encourage producers to "dump" cheap sugar on the world market.

COCOA + 80%

Cocoa, the main ingredient of chocolate, is the most political of all food commodities, growing best in tropical countries which are prone to hurricanes, El Niño and coups.

In 2006 it was being traded at around £896 a tonne; this year it peaked at well above £2,000. Part of the reason was Armajaro, a London-based hedge fund specialising in commodity trading, which last July bought around 240,000 tonnes of cocoa. This single transaction – worth around £650m – amounted to around 7% of annual global production and sent the price spiralling. It doesn't help that 40% of the world's cocoa comes from Ivory Coast in west Africa. Earlier this year cocoa shipments were disrupted during fighting between supporters of current president Alassane Ouattara and former leader Laurent Gbagbo following a disputed election last November. US commodity trading firm Cargill, which handles nearly 15% of the country's cocoa beans, stopped exporting cocoa when Gbagbo refused to step down – and prices jumped to nearly their highest in 30 years. Last month, with Ouattara installed, Cargill resumed exports and prices have dropped.

Meanwhile, the recession in Europe and the US has dented demand and there are concerns about whether supply can keep pace with growing demand as India and China develop a taste for chocolate.

COOKING OILS + 53%

Palm, soy, sunflower, rapeseed, maize (corn) and other vegetable oils have never been in such demand. Palm oil is now the most traded vegetable oil in the international market and its price hit an all-time high in 2008 when the oil price peaked. Because most vegetable oils can be used as biofuel for cars as well as cooking oils, their prices are determined partly by the price of crude oil and partly by fluctuating demand and supply. Most oils have risen more than 20% on global markets in the year following bad weather last year in Indonesia and Malaysia, the world's two biggest producing countries, and soaring demand in economically burgeoning China and India.

RICE + 33%

In 2008, the price of rice tripled to nearly $1,015 per tonne as oil prices soared and speculators moved in to bet on shortages of what is the staple food for nearly half the world. Rice prices vary according to where and when it is grown and the crop variety, but the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation has recorded up to 70% increases in the last year, while the Manila-based International Rice Research Institute says the figure is closer to 20%. More recent price falls have been mainly due to increased exports from Thailand, Vietnam and the US. This year, Cambodia, India and Bangladesh are expecting bumper crops. OFM

All price rises are May 2010 to May 2011. Figures from the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations