The seaside road was throttled by traffic heading towards Dog Temple, and cars were parked for several kilometres along the coastal highway. Unlike most shrines, where deities are worshipped during the day, worshipping ghosts is best done after midnight, when they are more likely to respond positively.

At midnight, tough guys who had rolled up in their Mercedes and BMWs, sauntered to the altar to pray on their knees. Young women in miniskirts and low-cut blouses, accompanied by bodyguards in leather jackets, placed incense in sacrificial urns and mumbled prayers, perhaps against the risks of their profession. The old prayed for the return of lovers long gone over the seas.

It was 1988, and I'd learned that a federal grand jury indictment had been issued against me, and the US was seeking my extradition on the grounds of my being the ringleader of the biggest cannabis smuggling organisation in the world.

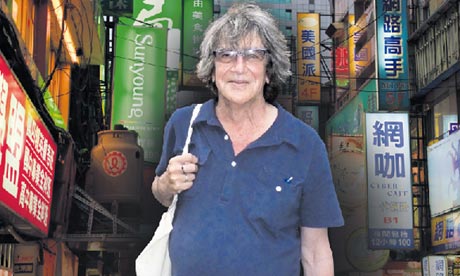

I'd never been to Taiwan, but I headed straight there. No one had ever been extradited from there to anywhere. I'd be safe. My first few days confirmed my optimism. I loved the place – there was no evidence of any law or regulation. Scooters and motorbikes carrying several passengers with no crash helmets careered through streets with no traffic signals and parked wherever they wished. Forgery was a respected profession. But I missed my kids desperately and kept thinking I should go home and wriggle out of the problem.

I heard tell of a Buddhist shrine – the Temple of the 18 Kings – patronised by lawbreakers seeking advice on criminal matters. I took a taxi there to resolve my quandary, and the driver explained that during the late 1800s, a boat carrying 17 fishermen and their communal dog capsized in the Taiwan Strait. The fishermen drowned, but the dog survived. In accordance with tradition, the locals prepared a collective grave and ghost temple on a cliff overlooking the shore. The dog jumped into the grave with the bodies, refused to leave, was buried alive, and became the 18th of the kings of the temple. Eighteen is the number of hells in Chinese folk religion. The temple was shrouded in safety, mystery, and danger.

Thick clouds of eye-stinging incense swirled around the temple's red columns. Altar candles burned in honour of a dog that signified luck and good fortune as well as loyalty and friendship. Worshippers lit cigarettes instead of incense sticks, symbolising the friendship between dog-spirit and man. They stroked and rubbed images of the dog. I made an offering of cash, cigars, and a Cartier lighter, bought a charm necklace, and asked the dog should I stay or should I go. The monk in charge gave me one of 64 possible answer slips. The taxi driver translated: I had to go home.

A few days later, I was in Madrid's terrorist prison trying to avoid extradition. I failed and spent the first few years of my possible 40-year incarceration vowing that should I ever get released, I would go back to Taiwan and kick that dog up its arse. Now, more than 24 years later, my daughter, Amber, was accompanying me there.

During the journey, I had scoured travel guides and brochures offering bungee jumping, trekking, shopping, fishing, cookery lessons, health spas and monasteries. But I know, through my decades of travelling, that the benefits of any action vacation become distant memories once you're back at work. Even worse are anti-vacations, with lean vegetarian diets, meditation, chanting and 5am alarm calls, where drinking alcohol is discouraged. I find such holidays vexing, mind-draining, and expensive.

I would settle my score with the dog, eat and drink. We checked-in to Hotel Quote in the centre of the capital, Taipei, an extremely efficiently run boutique hotel that was a finalist last year in the coveted Taipei's Best Hotel Bar after Dark award.

Dawn broke after what seemed like a few minutes, and I caught a fleeting glance of Amber tip-toeing out of the room. She was off to Sun Moon Lake, about 250km away in the centre of the country, for some peace and tranquillity. I fell back asleep and missed breakfast by at least eight hours.

Amber had left a note asking me not to go to the Dog Temple until she returned. As night fell, I took a taxi to the nearby Combat Zone, the only night-life area I remembered from my first visit. Almost identical to Bangkok's Patpong, the zone was a neon-lit concentration camp of more than 50 girlie bars and strip joints in a grid of small streets behind the Imperial Hotel. The zone got its start during the Vietnam war, when American soldiers partied there on their way to and from the killing fields.

Its boozy legacy survived, but it had aged considerably, and the tired no‑smoking bars and clientele lacked their previous libidinous lustre. I had a few interesting chats with some veterans who had never had any reason to go back home, while the wind picked up, howling like a flock of owls, and the pitch-black sky emptied. It was typhoon season, and one was hovering off the coast, threatening to visit. I, too, was feeling my age, and went back to the hotel to carry on sleeping off my jetlag.

At breakfast the next morning, I met an American, David Frazier, who wrote for the Taipei Times. He was an endless source of information on all Taiwanese matters, knew of the Dog Temple, but had never visited it. He offered to drive us there.

Daytime is never the most appropriate period to communicate with ghosts anywhere, so Amber and I were not surprised to find the Dog Temple, which I instantly recognised, almost deserted. But I was astonished to see that the temple lay next to Taiwan's first nuclear power station. David explained that the power station enclosure had been designed originally to encompass the area of the sacred tomb, but the heavy machinery broke down whenever it neared the shrine.

The engineers had to abandon their original plan and the nuclear station's outer wall simply borders the tomb. This helped transform the hitherto local cult into an island-wide craze. The shrine became a focal point for successful anti-nuclear demonstrations, eventually becoming one of Taiwan's most popular temples.

The cult of the dog in the 18 Kings temple is paradigmatic of the coexistence of tradition and modernity in Taiwan. The power generated by a nuclear reactor could not diminish that of a dog worshipped in a nearby temple. On the contrary, the reactor itself was incorporated into the legends celebrating the dog-spirit, and the modern media spread the legends throughout the island. There were simply too many visitors to cast them all as underworld types: many were simply ordinary people unconcerned about issues of morality. Bus and taxi drivers suspend temple amulets from their rear-view mirrors and place small statues of the robed dog-spirit on their dashboards.

But the carnival atmosphere for which this seaside temple was so famous had inexplicably faded. It looked a bit shabby, with just two food vendors in front selling unappetising bamboo-leaf-wrapped rice and meat dumplings, braised stuffed snails, and some worryingly unrecognisable roasted animal parts. However, a pack of stray dogs loitered knowingly.

Shaking with the trepidation of uncertainty, we walked slowly into the shrine. The six-foot high grey stone dog that had haunted me during my years of solitary confinement was no longer there. It had been replaced by two smaller bronze dogs, each baring their teeth savagely. I had already more or less decided not to give the big dog a hefty kick and fool around with a humbling power I did not understand, and in any event, the smaller dogs' arses were inaccessible. Their ferocious mouths turned into loving smiles. I put my right hand into one of their mouths. I was here, alive, healthy, and with my wonderful daughter. I could not imagine being happier.

Behind the altar, David and I climbed a hidden stairwell to a small, dark room above the temple, where we discovered a cabinet with 64 small draws, each containing a pile of small pink paper slips bearing a fortune.

David, fluent in Mandarin, searched through the 64 different possible answers the dog spirit could give. One stated: "Travellers will find benefit in returning home. If burdened by legal affairs, settle them peaceably." Clearly, that was the one I had received in 1988.

We looked at the pink slip again. Printed in smaller type next to the larger fortune was the following: "This sacred word will bring luck to one of noble heart. But for a scoundrel it will bode ill fortune. Many contradictions are apparent. The return of good fortune cannot be determined." David burst out laughing: "You obviously didn't read the fine print, Howard."Later, at the end of our trip, he phoned me minutes before we boarded the plane to London: "I've found out that a second temple has just been built the other side of the nuclear power station."

"Don't tell me that's where the six-foot grey dog statue is," I said.

"No. This one is two storeys high. I don't know how we missed it."

The hotel concierge had suggested I eat at a typically Taiwanese restaurant with the unlikely name of 21 Goose & Seafood, on Jinzou Street, a road that was full of bars and restaurants heaving with rowdy clients. Every table was occupied, but a table for two had a vacant chair to which I was directed. The lone diner stood up, shook my hand, and in stuttering English introduced himself as Li.

No smoking signs blazed from every wall, but everyone without exception, including the chefs, was smoking. A betel-nut vendor passed from table to table offering his wares. The set menu was the same each night, first course: goose, second course: seafood. Li and I small-talked for a while as more people crowded into the restaurant and somehow found space. He suggested we go to the bar next door for a drink. The street activity had increased even further when we went outside.

Wasn't Taiwan supposed to be suffering in recession like the rest of us? Over the past few years, I had read several uninviting headlines about unemployment being at an all-time high, economic growth at an all-time low, a severely battered stock market, Sars viruses replacing visiting businessmen, and more bad news. Yet here they were spending money all night, eating jovially, exchanging phone numbers, and drinking with ebullient enthusiasm in crammed bars and restaurants filled with an atmosphere of revelry, intoxication, and fun.

"Taipei busier than ever," said Li, noting my looks of astonishment at the dynamic chaos. "When Taipei people worry, they drink. But rest of Taiwan, bars and restaurants struggling. Sales no good. Places closing, pushing each other out of business with bargain price and happy hour. Even here in Taipei, must sell entertainment, too. Not just booze."

I looked at the four Chinese women dancing on the bar, caught his drift, and nodded over to them. "Like paying that lot to do their thing?"

"No. They just office girls having good time. Bar pay for music, lights, smoke vapour, and beautiful girls for customer. Technique simple. Girls surround customer. He buys them drink. They come closer. He buys more. Chinese have special name for feeling of being surrounded by seduction, to be lost in company of beautiful women – mi huen zhen. Room next door, karaoke. Upstairs different entertainment."

Upstairs housed an open-air smoking area. Several satellite dishes fed enormous plasma screens, showing a steady stream of football games, Formula One races, and tap dances to a crowd of foreigners playing table football, pool, and darts. There was no dartboard, just punctured pictures of Karl Marx, and Fidel Castro. The male foreigners were outnumbered by Chinese of both genders looking on in noisy amazement and occasionally throwing a dart and drinking a yard of beer. Peanut shells, dog ends, and sawdust covered the floor.

"This new in Taipei," said Li. "Taiwanese like new."

Another evening, pulling up alongside a heavily populated pavement, we were greeted by immaculately dressed waiters bringing us menu cards to fill in. They would find us when our table was ready. Din Tai Fung is the most famous restaurant in Taipei. There are dozens of cooks looking like surgeons, heaps of bamboo steamers, and great piles of pork and dough rolled and wrapped into its signature dish – the dumpling – thin and fresh, never soggy or doughy, and served immediately after it is steamed.

The most popular is also the most basic, made with green onion, ginger, pork, soy sauce and sesame oil. The floors and furniture were cleaner than any I have ever experienced, including those of top-end private hospitals and clinics. After taking our seats, we were politely but thoroughly instructed which dumpling went with which sauce and the order in which to eat them. The bright lights helped ensure a quick turnover. One comes here to eat, not for romance.

Taipei has an advanced 24-hour snacking culture enabled by street vendors, who will show up wherever people gather, whether at temples or cinemas. Simplicity and freshness are the hallmarks of Taiwanese street food. It's fresh because the turnover is high, and simple because each stand concentrates on a single dish.Most of the stalls are basic set-ups with a few stools, a generator, a tank of cooking gas, and a grill, pot, or steamer.

Although grilled sausages and squid, with their smoke and flame, are the most visible street food, a Taipei night market will also have stands selling fried rice, congee, grilled beef, oyster omelettes, wheat gluten, onion pancake, barbecued pork, roast chestnuts, fresh juice, and dumplings.

Some of the street food comes from extreme ends of the food chain and looks more like a biology field trip than dinner: entrails, innards, wings, knuckles, feet, tongues and congealed blood are common. Wafting down every alley and byway in Taipei is the unmistakable and often appalling odour of stinky tofu, best eaten when smothered in soy, vinegar, garlic and chilli sauce.

Most Taipei restaurants, however, no matter how good, are featureless, except for those that concentrate on one feature: Tai G, in the Shipai night market, serves just medicinal chicken soup, tailored to the customer's particular ailment. Jail (37 Dunhua South Road) is decorated like a prison and the waiters dress like inmates. Visitors can put on manacles and have their photo taken in a cell.

I gave both of those a miss, but did try Snake Alley – which is a narrow covered passageway where writhing snakes are skinned alive so that people can drink their warm blood while scoffing snake stew – and Modern Toilet (Lane 50, Xining S Road), which has seats and serving dishes shaped like toilets. The food in each was disgusting.

I found the Taiwanese very friendly and relaxed. One can occasionally think Taipei has been far too busy making things to offer anything at all to visitors. But what it does have is genuine, and everything you do see is for the daily lives of the Taiwanese. There is nothing fake for tourists, mainly because there are so few of them.

• The trip was provided by Cox & Kings (0845 154 8941, coxandkings.co.uk). Its 13-night escorted group tour to Taiwan costs from £3,002 per person, including flights from Heathrow to Taipei with Eva Air, transfers, excursions and accommodation on a half-board basis plus some other meals. Flights were provided by the Taiwan Tourism Bureau (eng.taiwan.net.tw)