Britain is full of breweries. According to figures from the Campaign for Real Ale, there are now 1,009 in the UK, more than double the number a decade ago. A nation with one of the richest brewing heritages in the world has fallen back in love with beer.

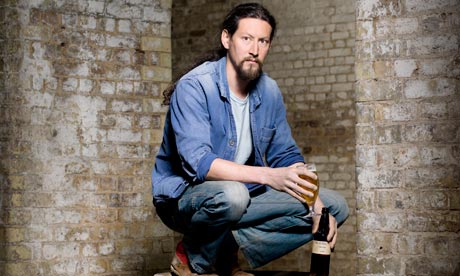

But how easy is it to set up on your own? Evin O'Riordain, founder of the Kernel, based in Bermondsey, London, knows better than most. Opening in 2009, he has become one of the most respected small brewers.

Brewing begins at home

O'Riordain, 38, began homebrewing after a trip to New York in April 2007. Trying it out himself was crucial to discovering how to reproduce the intense, citrus-hop flavours he had enjoyed in the US. "It took me a while," he says. "The first batch was decent, but it was only after about 12 brews that some started coming out really well."

Make new friends

O'Riordain also learnt some key lessons as a member of London Amateur Brewers. There are brewing faults you might miss, he says, such as diacetyl (a buttery taste caused by a flawed fermentation) that others are more sensitive to. "It's important to have people who critique your beer in an honest way," he says. "The first rule at London Amateur Brewers was: don't say anything nice. Be slightly harder than you would be normally, so we can dig out what's happening. How do we fix it, make it better? That's how you improve."

But don't forget your old ones

Having been a cheesemonger at Neal's Yard Dairy, O'Riordain knew people in the food industry and those contacts helped him find a site for the brewery. "Neal's Yard let us know that there was an arch going in Druid Street, next to where they were," he says.

At first, he brewed once a week while continuing to sell Gorwydd caerphilly at Borough Market on weekends. "The only way people knew about us was word of mouth. That first year, Neal's Yard sent 10 bottles to all their favourite customers at Christmas. There's quite a few who are still customers now." He has since repaid that kindness to fellow brewers: last year he donated his first professional brewing kit to fellow Bermondsey brewery Partizan.

Find the right kit

O'Riordain bought his brewing equipment from Porter Brewery Installations, whose smallest kit – containing everything you'll need to get started, and producing 400 litres of beer with each brew – costs £10,600. The Kernel started on a slightly larger, four-barrel kit (600 litres a brew), which costs £15,100. The price includes a demonstration brew, crucial for those whose experience of professional breweries is non-existent. If you're short of funds, it's possible to start even smaller: down the road from The Kernel is Brew By Numbers, who began with a tiny kit in a Southwark basement, which allowed them to build a reputation before any serious investment.

When it comes to flavour, keep it simple

The New York trip helped O'Riordain decide the sort of beer he wanted to make: clean-tasting and hop-forward, unlike most of those then available in the UK. "American hops have a certain intensity," he says. "You use a very clean yeast and it becomes a platform for the hops."

Experimentation has its limits, he believes: "There's something very engaging about it, but the results aren't always there."

The costs can mount up

High rents can be a problem when looking for a space. "Initially it's a bit tough, but as long as your rent is fixed for the foreseeable future, you can plan for it."

O'Riordain also spent £15,000 refitting his arch: this included electrics, flooring, plumbing and drainage. The most basic bottling equipment costs £500 and even the bottles for his initial brew cost £200.

Then there's beer duty, something that is partly offset by small breweries' relief, which gives a sizeable tax break to smaller breweries. It's one reason why it's important to have people around you who understand the financial side. "I rely on my accountant," O'Riordain says. "We're making enough money to survive, to pay everybody who works here a good wage. That's the bottom line."

Bottling is a tedious business

Initially The Kernel bottled by hand, which means labelling, cleaning, filling and capping each one. "It's the banality of it that sticks out," says O'Riordain. "You get to know the person next to you very well when you're bottling." He now has a bottling machine, which cost £65,000.

Trusting people pays off

The Kernel's approach is about transparency: the brewery is open to the public on Saturday mornings, they don't advertise, and deal directly with many stockists. Even the labelling is functional: sparse black printed on brown paper.

Remarkably little promotional work has been done, considering the brewery's level of success (he's now brewing four times a week). "It's to do with having a little bit of faith in humanity," says O'Riordain. "We don't tell people what something is going to taste like: people can make that decision themselves."

Not all modern brewers are so laidback and there are other, more obvious routes to success. Fraserburgh's Brewdog has used humorous, sometimes aggressive marketing to make its point. It's worked: Brewdog recently opened a new £8m brewery and has 11 bars in the UK and one in Stockholm.