So, on one thing at least, Nicolas Sarkozy and David Cameron are agreed: 2012 is going to be tough. Another hole will have to be punched in all of our belts. For them personally, of course, life will change not one iota (though Sarkozy might, I suppose, lose the presidential election). Cameron, seated at his Eero Saarinen marble table, will go on eating the sugar-free jam ordered by Sam from Waitrose, and Sarkozy will continue to visit Restaurant Guy Savoy, which has three Michelin stars, and a Thai place he favours called Thiou, in the 7th arrondissement. But the rest of us, stalked by fear as we prowl the frozen foods aisle, are going to have to watch it.

How to quell the hum of anxiety? The obvious way is to swot up on cheap food – to remind yourself that neck of lamb, done right, is the next best thing to heaven. Ditto chicken livers, and proper rice pudding. There are tons of austerity cookbooks around, but if looking for one, my favourites are The Pauper's Cookbook by Jocasta Innes – buy the 1971 Penguin on Abe; the "updated" edition is not half so good as the original – and The Full English Cassoulet by the great Richard Mabey, who took up foraging decades before sea kale appeared on any metropolitan menu. Some people favour Delia Smith's classic Frugal Food, but its tone just makes me want to max out my credit card buying white truffles.

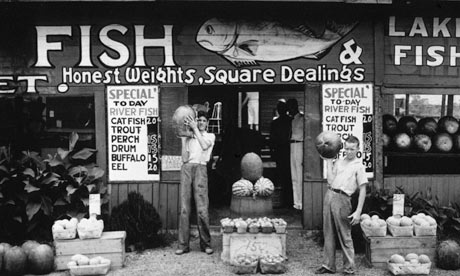

Or consider the past. While I was thinking about this column, I found a book I bought a while ago: The Food of a Younger Land, which is a collection of writing from across America, each dispatch dating from the late 1930s (the pieces were commissioned by Roosevelt's Federal Writers' Project, a New Deal make-work scheme for writers, among whose number were thousands of unemployed newspapermen and their secretaries, but also Eudora Welty and John Cheever). Reading these reports – they were recovered from the Library of Congress and edited by Mark Kurlansky in 2009 – is chastening: at the time they were written, some Americans had only recently been in danger of starving to death, and there are recipes here so hardscrabble, the stomach hollows at the thought. But this is also America before Burger King, before Pop-Tarts and industrial-sized freezers: the food it describes is seasonal, regional and, mostly, it sounds good.

This is a lost world brought to life vividly: squirrel mulligan from Arkansas, Brunswick stew from Virginia (made with flying squirrels, as opposed to the regular scurrying kind), fried beaver tail from Montana, and prairie oysters (calf testicles) from Oklahoma. There are Native American influences – the largest kind of New England clam is the quahog (the word comes from the Narragansett) – and immigrant influences, too: chorizo in Idaho, where Basques came to work as shepherds, and lutefisk suppers in Minnesota, where Scandinavians settled (lutefisk is a gelatinous dish made from dried whitefish). More predictably, there are several ways with hominy grits, chitlins, persimmons and mint juleps (my favourite: the julep recipe of Mr and Mrs Billups of "Whitehall", Columbus, Mississippi, which begins with the instruction: "Have a silver goblet thoroughly chilled").

The FWP's investigation into America's food culture was abandoned in 1942 following the attack on Pearl Harbor, with the result that no one ever got to read its cry against "standardisation" – or to take the advice of one of its writers, who urged travellers to knock on local farmhouse doors should they find themselves fobbed off with bland, substandard fare on the road. Rather, the nation went loopy for Jell-O and cake mixes and, in the fullness of time, the fast food joints that adorn America's highways.

Reading these dispatches now is to experience a sense of loss, and for something – clambakes! – one didn't know in the first place. But it is also, in the context of Cameron's gritted teeth ("I get it," he says, as if we don't), strangely consolatory. The thought occurs that choice, innovation and a certain kind of abundance made paupers of Americans – and, eventually, of us, too – long before this recession started its work. What goes around comes around. We will get by somehow, just as our grandparents and great-grandparents did before us. And if the tightening belt puts the squeeze on us to try new things, which are, in fact, old things, then this can only be a good thing.