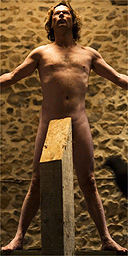

I do feel a bit like I'm building my own gallows,' says Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall. He's helping OFM's photographer build a set for his portrait in a barn on his Dorset farm. He is equally reluctant to strip off for the camera. Fearnley-Whittingstall feels exposed enough already, frankly. Surely he must have faced more nerve-racking moments in the last year, making his latest series, Hugh's Chicken Run, about intensive poultry farming?

'There were certainly moments of doubt, especially about creating our own intensive chicken farm,' he says. 'On different days there were different anxieties. On the one hand I was doing the opposite of what I would normally do when raising chickens. For me, putting in an order for two-and-half-thousand chicks and knowing they weren't going to have a very nice life felt very weird and paradoxical and of uncertain outcome. But I also wondered whether the intentions behind it would be understood or whether people might have thought it was an over-dramatic or attention-seeking or gratuitous way to approach the issue.'

Chicken Run was a world away from Fearnley-Whittingstall's gentle River Cottage series which detailed his life on a working farm, and which turned him into a one-name-celebrity, a 'Hugh' to Jamie Oliver's 'Jamie'. But it also makes sense, in the grand scheme of his work. Fearnley-Whittingstall is a vociferous campaigner for traditional, ethical farming methods. Channel 4's River Cottage created a middle-class obsession with the idea of 'locally sourced' food; and it engaged us with the rearing and killing of farm animals. Fearnley-Whittingstall made us appreciate how passionate local producers are about their food, and how incredibly hard they work at it. Later programmes helped us connect still more with our food by looking at how we can eat fish sustainably, how to grow your own or forage for greens; and he's taught a new generation of viewers about the value of seasonal eating. Perhaps, most significantly, through River Cottage and Chicken Run, he has married the disparate worlds of rural and urban Britain. He's connected us to the food we eat, and to the broader issues around the ways that we consume.

That's not to say he isn't aware of his limitations: 'It's really impossible not to be a hypocrite with these things. One can never get it right all of the time. You convert your car to LPG and then you feel like you should be in a horse and cart. Or you get a wind turbine and someone tells you it will take 100 years to generate as much energy as it took to build. What can you do? However, although it's frustrating, it's better to worry about these things than to ignore them. I'd rather be rearranging the deckchairs on the Titanic than sitting at the front smoking a fat cigar.'

Chicken Run was a gamble. 'We're not the first people to have looked at the poultry industry and thrown up our hands and asked consumers: is this really what you want to eat? But in the past, it's tended to be current-affairs documentaries with clandestine filming, programmes of a sort that either people find too dry or that they deliberately shut out because they don't want to know. Or they do know, but it washes over them: they think, "It's not relevant to me and my chicken in my supermarket because I'm sure they're quite nice." I think that by personalising it, and by me being quite affected by it at times, makes it clear that it absolutely is relevant to you in your supermarket if you buy that kind of chicken.'

Chicken Run has had an impact. 'Informally, we've had lots of reports that sales of free-range and organic chickens are increasing since the programme went out; and formally from Sainsbury's who've said their free-range and organic birds are flying off the shelves. We've also heard from the biggest poultry producer in the West Country, who does organic, free-range and Freedom-Food chickens, that they can't keep up with the demand for free-range because the supermarkets have been increasing their orders.'

Fearnley-Whittingstall is not without his critics. Not everyone can afford to buy free-range chickens or the organic and locally produced food that he advocates so passionately. 'There are two aspects to the price question. There's the "it's all right for him, he's double-barrelled, went to Eton, has a nice farm in Dorset and a cushy job on the telly, he can afford free-range chicken" aspect, and I think that's irrelevant. But if by extension you're saying, "well, it's all right for people who lead a comfortable life and can afford to buy free-range chicken", then OK, even if we only accept that argument, surely 30 or 40 per cent of us could afford free-range chicken - when actually it is only a tiny proportion of us who do. Less than five per cent of chickens are free-range in this country.'

Nonetheless, by taking Chicken Run to an estate on his local town of Axminster where he set up a free-range chicken run with the locals, he was taking the argument to people who didn't feel they could afford free-range chicken. 'Animal welfare isn't a class issue, or even an economic one, it's an ethical issue and people on a very low income have ethics. We've had some amazing letters from people on income support, who are jobless, or who are single mums, saying, "Don't let anyone tell you that people with no money don't care about chickens." I had one in my hand this morning, saying, "I have to feed my family on £35 a week, but I still wouldn't dream of buying an intensively farmed chicken."'

Fearnley-Whittingstall argues that our expectations need to be changed. 'If you didn't know about two-for-a-fiver chickens, £6 for a free-range chicken would be one of the great bargains of meat, because you can feed a family twice off that. And if you compare it with intensively farmed pork, or most red meats, free-range chicken is a great bargain. It isn't that free-range chicken is expensive, it's that intensively reared chicken is ludicrously, and I would say shamefully, cheap.'

Fearnley-Whittingstall is aware this battle has only just begun: 'All we've done with the chicken campaign is to start a conversation. But we think it's an important one.' For taking on the might of the supermarkets, and for forcing us to think about the meat we eat, we salute him.