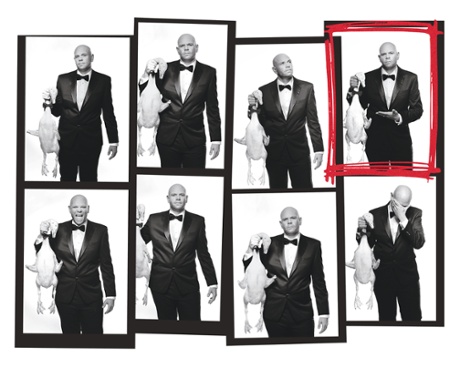

Tom Kerridge can’t quite put his finger on where it all went right. Five years ago, there he was, 37 years old and minding his own business at his pub in Buckinghamshire, and now look at him: The Hand & Flowers in Marlow is the only pub in the country to hold two Michelin stars, and he’s a bestselling author and TV sensation. He ponders for a second or two before unleashing that now famous Kerridge grin: “Actually, it’s all Great British Menu’s fault.”

The BBC programme came calling in 2010, when it was scouting around for new talent to appear in its fifth season. To begin with, Kerridge saw it purely as a marketing opportunity. “We’d survived the worst of the recession,” he says, “and this seemed a no-brainer. It was fantastic exposure for a little business like ours.”

It turned out to be a lot more than that. Kerridge, like any chef worth his salt, has a formidable work ethic, and he applied himself to the show “as seriously as everything else to do with work. Luckily, I didn’t feel awkward or out of my comfort zone in front of the cameras, either – I’ve always been confident with just being me.” When you do television, he says, viewers invite you into their living room, “so you’ve a responsibility to be true to yourself, otherwise they’ll see straight through you”. It also helped that television is a lot like a kitchen: “There are all sorts of people involved behind the scenes, and they’re all essential to the process.”

It wasn’t just the viewers who bought into big Tom; the judges did, too: Kerridge’s slow-cooked Aylesbury duck with duck-fat chips and gravy went on to win 2010’s main course prize. The following year, he repeated the trick when his hog roast waltzed off with same accolade. That’s when things really kicked off. The same year, the Hand won its second Michelin star (the first, in 2006, had come a year after opening), and Kerridge was suddenly a household name. “The first star put us on the map, and the telly was great for our UK profile,” he says, “but the second one put us on the international stage.”

Not bad going for a guy who made two roast dinners on TV. The choice of those dishes, however, was very deliberate. “The Hand is a pub, always has been, always will be,” he says. “The Coach [his second Marlow pub, which opened at the end of last year] is, too. I can’t be doing with that old-fashioned restaurant culture where diners feel intimidated.” This philosophy shines through his menus – a recent à la carte at the Hand featured gala pie and apple and custard slice, which aren’t exactly the first dishes that spring to mind when you think Michelin. Granted, they’re not quite the same as the ones you get at Greggs, but still.

The weird thing is, Kerridge never planned on being a chef. “I was 17, 18, and just needed a job and some cash. All this is just a pleasant accident.” He can say that again. He grew up in Gloucester, with his mother and younger brother. “After Mum and Dad split up [he was 11 at the time], me and Sam lived with Mum. She did two jobs to make ends meet, so we were basically latchkey kids. When we got home from school, it was my job to make our tea before Mum got back. I wasn’t baking a lovely pie from scratch or anything like that, more getting something warm inside us – beans on toast, jacket spuds, that kind of thing – but even then I enjoyed the sense of achievement you get from physically feeding another person.”

At 16, he got his first glimpse into the mysterious world of restaurants as a part-time pot-wash, to earn himself a bit of spending money, and at 18 he started in a kitchen proper. “I loved school,” he chuckles, “but no one who knows me would ever say I was academic.” The day he started was a lightbulb moment. “I immediately loved everything about it. The adrenaline, the noise, the social life – the idea of going out after work for a few pints in some dingy bar, when everyone else is already tucked up in bed, gave me a real buzz. I even loved the silly hours.” He could have done any job, he says – carpenter, fisherman, whatever. “I’d have still worked as hard. I’ve never minded graft.”

By the end of the 1990s, he had stints with Stephen Bull and Gary Rhodes under his belt, both of whom helped shape his cooking ethos. “They had none of that pomp and ceremony you get with fine dining. That really rubbed off on me. It gave me a classical training, but in an environment that suited me down to the ground. It’s all very well having fillet steak on the menu, but what about the rest of the cow? The shin, cheeks, ribs …”

But the most important factor in any restaurant isn’t the food, he says, it’s the people, customers and staff alike. “If you don’t get the right sort of either, you may as well pack it in.” And, boy, does his brigade buy into the Kerridge ethos. The Hand’s head chef Aaron Mulliss and general manager Lourdes Dooley have both been with him for eight years, and he racked up all of 14 with pastry chef Jolyon d’Angibau – this in an industry where a two-year stint in the same kitchen is worthy of a long-service certificate.

All this talk of friends and colleagues brings him to the most important member of his support network. “Of course,” he laughs, “it’s not really Great British Menu’s fault at all. It’s mostly the wife’s.” He met Beth 18 years ago, when he was cooking in London and she was working for Sir Anthony Caro. “My best mate was the brother of one of Caro’s tech guys, and we were introduced at his birthday.” They married three years later, and it was Beth who persuaded him to go it alone at the Hand in the first place. “She said, if I was going to work so hard and such long hours, wasn’t it about time I started doing it for myself. It hasn’t been all plain sailing, but I wouldn’t be in this position today if I didn’t listen to my wife. We’re a good team.”

Part of the point of buying the pub, he says, was that there was plenty of space for Beth to do her art but, as things turned out, she spent the first two or three years running the front of house. “Then the recession hit, and she ended up working her arse off just to keep the business afloat. It’s only with the success we’ve had in the past five years that she’s been able to step back and concentrate on her own work for a change.” (Not uncoincidentally, Beth’s career has since flourished: her latest solo show is at Gallery Different in London at the end of the month.)

He insists, however, that the success – the stars, the TV, the books and fame that comes with them – is secondary: his passion is still to put food on a plate that people want to eat. “It’s not rocket science,” he says. “When people go out for a meal, they’re looking to have a good time. And, as the chef, you’re the provider of that good time. What could be better than that?”

Tom Kerridge’s chicken casserole

This is one of the easiest but also one of the tastiest chicken casseroles you will ever make – it is a one-pot wonder and a great family treat. Based on the classic French poule au pot, it packs in a whole lot of flavours and textures. If you have any of the lovely stock left over, freeze it to use in soups or sauces later.

Serves 4-6

chicken 1 medium, about 1.5kg, giblets removed

carrots 2, each cut into 4 pieces

celery sticks 2, tough strings removed with a vegetable peeler, each cut into 4 pieces

white cabbage 1 small, about 350g, quartered

leek 1, trimmed and well washed, cut into 6 pieces

celeriac ½, peeled and cut into 4 pieces

pickling onions or small shallots 8, peeled and halved

garlic cloves 8, peeled but left whole

salt and freshly ground black pepper

cured garlic sausage 1, about 200g, cut into 1cm dice

smoked lardons 100g

thyme ½ bunch

rosemary 1½ bunch

fennel seeds 1 tsp

black peppercorns 1 tsp

star anise 1

chicken stock 700ml

Preheat the oven to 170C/gas mark 3½. Season the chicken cavity lightly with salt. Put all of the vegetables and the garlic into a large bowl and season with salt and pepper. Toss to mix.

Scatter a layer of vegetables in the bottom of a large, heavy-based flameproof casserole and place the chicken on top. Pack the remaining vegetables, garlic sausage and lardons around the chicken and tuck the thyme, rosemary, fennel seeds, peppercorns and star anise into the pot too.

Pour in the chicken stock. Put the casserole over a medium-high heat and bring to the boil. Cover with a tight-fitting lid. Place in the oven and cook for 1½ hours. Remove from the oven and leave, covered, to rest for 20-30 minutes.

Carefully lift the chicken from the casserole and place it on to a baking tray. Use a cook’s blowtorch, if you have one, to colour the skin until it’s golden. (This isn’t essential but it will add colour to the dish.)

Shred the chicken into large pieces and divide it and the vegetables between warmed deep plates. Ladle over some of the broth and pour the rest into a warmed jug to pass around the table.

Extracted from Tom’s Table by Tom Kerridge (Absolute Press, £25). Click here to order a copy for £17.50 from Guardian Bookshop